- Details

-

Published: Tuesday, March 04 2025 01:40

Alaina Green is happy to face a challenge. Before becoming one of Joint Quantum Institute's newest Fellows, she cruised around the Atlantic in a 34-foot sailboat with only her husband, occasionally facing waves as tall as a two-story building.

“It was a little bit scary at times,” says Green, who is also a physicist at the National Institute of Standards and Technology and a UMD Assistant Research Scientist. “We'd have these waves come up, and because they were so tall, they would be above us. One time we saw a dolphin—just like, I was looking up at a dolphin.”

When she isn’t navigating the open sea, Green spends most of her time facing the challenges of lab-bound quantum computers—meticulously aligning lasers and wading through pages of mathematical calculations. In fact, the difficulties she found in physics were what originally drew her to the field.

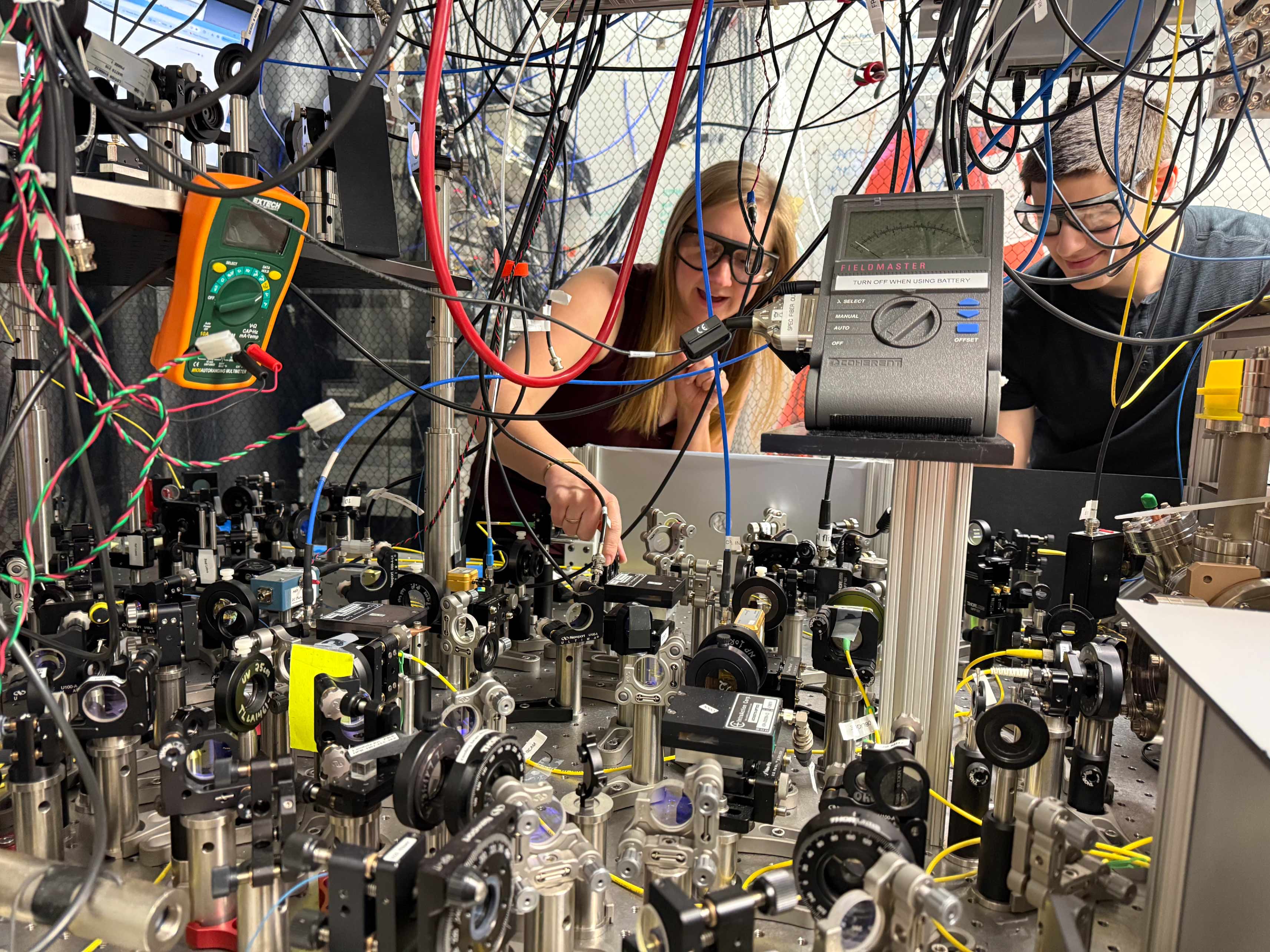

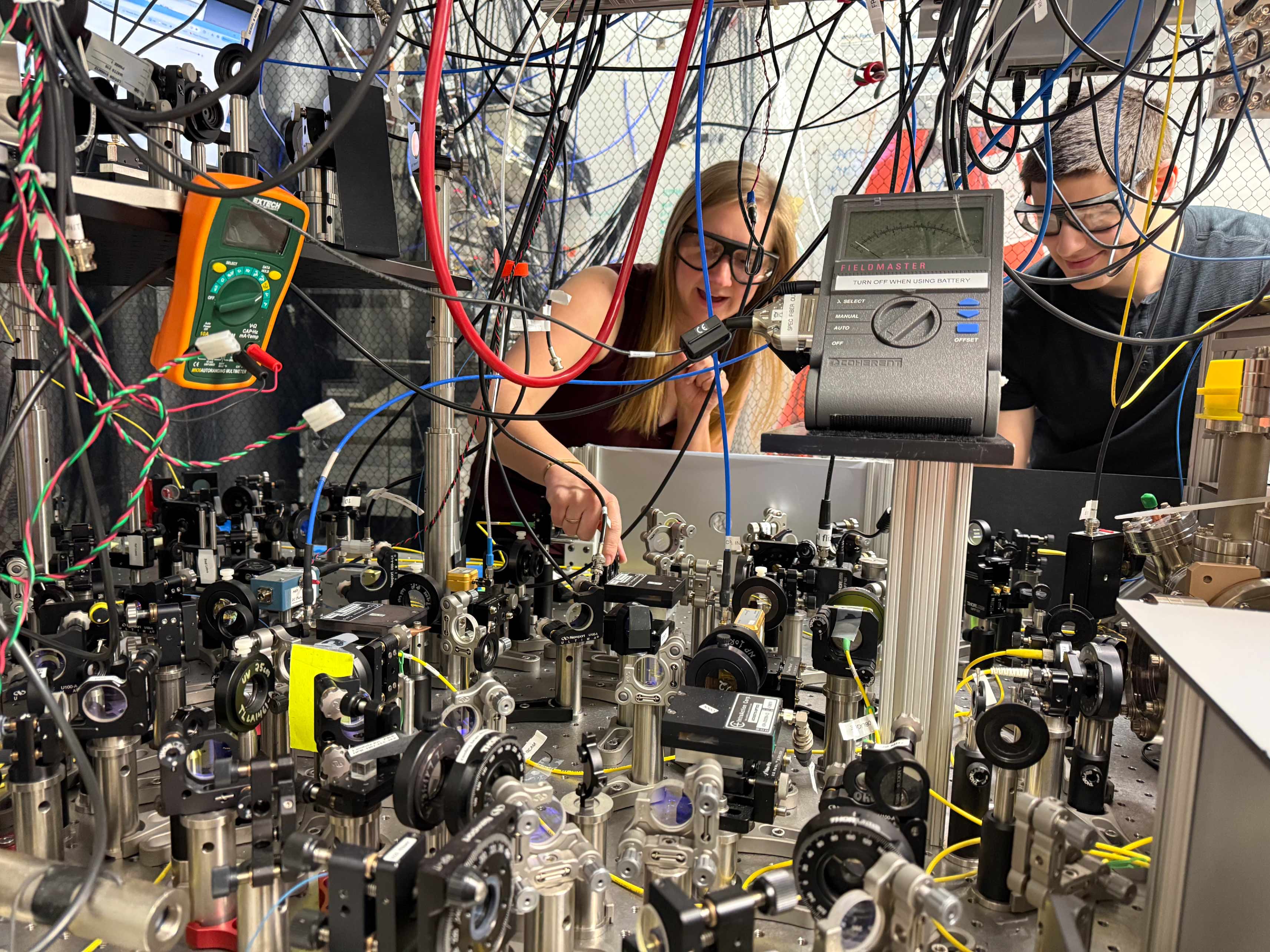

“When I was getting ready to go to college, I was actually really on the fence about whether I was studying literature or physics, which is crazy,” Green says. “Ultimately, I chose to study physics because it was a little bit harder. I've always scored better on my reading and writing tests than my math. I really enjoyed both of them, but physics was more of a challenge.” Alaina Green with UMD graduate student Matthew Diaz working on an equipment in Green's lab. (Credit: Connor Goham)

Alaina Green with UMD graduate student Matthew Diaz working on an equipment in Green's lab. (Credit: Connor Goham)

That decision led to her studying physics and working in physics labs as an undergraduate at Lewis & Clark College in Portland, OR and as a graduate student at the University of Washington in Seattle. In those labs, she learned how to use lasers to manipulate atoms and molecules and study both their properties and environments. Then she joined JQI as a postdoctoral researcher and began to use lasers as part of a trapped ion quantum computer, which relies on lasers to manipulate ions—electrically charged atoms.

“Dr. Green is a perfect fit for JQI,” says former JQI Fellow Norbert Linke, who was recently announced as the next director of the University of Maryland’s National Quantum Laboratory and whose lab Green worked in as a postdoctoral researcher. “Her background studying molecule formation in ultracold atomic gases, combined with her recent achievements realizing a diverse array of innovative quantum computing and simulation experiments in trapped ions, makes her an ideal JQI Fellow.”

In Linke’s lab at JQI, Green worked on getting the lab’s quantum computer running as reliably as possible and creating new applications for it. But as she makes her research plans for her own lab, she believes that the work of building bigger and better quantum computers is quickly becoming more suited to industry labs than academic experiments.

“I can't just build another quantum computer, which I think is slightly better, because I know that there are multiple companies who are going to be attempting to do that in order to satisfy their customers,” Green says. “But what I can do is go back and ask some more fundamental questions.”

Green has decided to apply the power of quantum simulations to studying quantum errors and how to correct them. Error correction is currently a major research topic since it is crucial to making quantum computers reliable enough to be widely useful. But Green doesn’t want to primarily focus on improving a computer by eliminating and correcting errors, which is a common approach in quantum computing research. Instead, she wants to build a quantum computer that intentionally fosters errors in simulated environments.

“I'm going to be using my atomic physics expertise to create these sorts of simulated environments, which I can controllably interact with my fairly good but not perfect quantum computer,” Green says. “I want to create this meta-simulator where you can say, ‘Okay, I'm going to have a bunch of this error, and I'm going to see how does this error correction protocol work—does it work?’ I sometimes call it my very bad, no good, horrible quantum computer.”

Using her computer, Green plans to systematically study errors. There are many different types of errors that pop up in quantum computers, and researchers have different proposals for the best ways to deal with them. Creating errors under conditions she controls will help her understand them and explore which error correction approaches work best in practice.

Creating Errors on a Firm Foundation

At first glance, Green’s goal of creating errors might not seem like much of a challenge since quantum computers are notoriously fickle and prone to errors. The slightest shaking or fluctuation of temperature can disrupt their operation. The difficulty in Green’s new project lies in creating errors that are convenient to study.

Intentionally letting a quantum computer heat up or shaking its lasers will induce errors, but those errors aren’t useful for the systematic study Green plans to undertake. Deliberately creating a specific type of quantum error on demand isn’t trivial but instead requires a similar level of care and expertise as keeping accidental errors in check. Creating useful errors with her quantum computer will be every bit as challenging as her past quantum simulation projects.

In her new computer, she plans to repurpose elements from some of her postdoctoral work performing quantum simulations—using a quantum computer to mirror the behaviors of another physical system. In particular, there are two notable examples of techniques from Green’s work in Linke’s lab that she expects to play important roles in creating useful errors.

One is a project where she and her collaborators performed a simulation of paraparticles—a hypothetical type of particle postulated by physicists in the 1950s. Paraparticles aren’t going to feature in her computer, but the tools Green and her colleagues used to simulate them will.

To simulate paraparticles, the researchers had to look outside the well-known toolbox of ways to make the various pieces of a quantum computer interact. The standard building block of a quantum computer is a qubit that can exist in multiple states at once (a potential upgrade from regular computer bits that must always be in one of two distinct states). However, the various designs of quantum computers generally include elements that aren’t currently utilized, but those pieces can still be put to use if a researcher knows their computer well enough.

In their paraparticle simulation, Green and her colleagues utilized previously untapped elements of their trapped ion computer that behave as bosons. Bosons are a category of quantum particles characterized by their ability to crowd into the same quantum state. The willingness of bosons to share a state allows them to behave very differently from ordinary qubits, which are built to behave as fermions and thus can’t share the same quantum state.

“There was this new resource of the bosonic degree of freedom, just kind of sitting there,” Green says. “Everyone has access to it, and no one was using it. And so, I felt really proud to be one of the first people to produce an interesting simulation using both the qubit degree of freedom and the boson degree of freedom.”

Moving forward with her new quantum computer, she plans to once again take advantage of the bosons present in her experiment. By using bosons to model an environment that can interact with the normal qubits, she can perform error-creating simulations without dramatically increasing the size of her computer. In December 2024, Green and her colleagues posted a paper on the arXiv preprint server describing their use of the approach to efficiently simulate subatomic particles interacting and sharing energy in one dimension. This experiment paves the way to more complex simulations involving interactions with the environment, including those related to quantum errors.

A second experiment that Green worked on in Linke’s lab will provide another crucial tool. In it, she and her colleagues developed a technique for managing the temperature of a quantum state in pursuit of quantum simulations of black holes.

Black holes, which are so big they warp space around them, are about as different from the tiny, delicate qubits of a quantum computer as you can get. Surprisingly, some theories describing black holes bear a notable resemblance to theories describing qubits, particularly when it comes to their temperature and the ways that they lose information. In both cases, information is intimately tied to energy and isn’t something that can be simply erased. Instead, it becomes harder to access over time as energy moves around.

“There are these very deep and intimate connections between black holes and quantum computers, which sounds crazy,” Green says. “But it’s actually true.”

Based on the similarities, researchers have proposed quantum simulations to model black holes from the comfort of a lab (an appealing option compared with trying to glean information across astronomical distances). The various proposals require that states at two different points in time during the simulation come together and interact. The theoretical models also predict that in both cases the temperature will affect the rate at which information is lost, so the simulations must create quantum states at several distinct temperatures to explore the theory fully.

A quantum state will naturally change based on the temperature of its surroundings, but the process is generally messy. Just exposing qubits to a specific temperature may get researchers a quantum state at that temperature, but it is unlikely to be a specific desired state, such as one carefully chosen to simulate a black hole. So, the team wanted to develop a reliable way to create a desired quantum state at a desired temperature on command.

Green and her colleagues didn’t perform a full simulation of a black hole, but they did figure out a way to craft quantum states corresponding to specific temperatures. The key to creating states at a desired temperature was the addition of qubits, which are each dedicated just to controlling the temperature of a single quantum state. The additional qubits make the simulation a little harder to run but effectively gave the group individual thermostats to control the temperatures of certain states. They successfully demonstrated the technique by deploying it in experiments that brought states from two points in time together, as is needed for future black hole simulations. The temperature control allowed them to show that information became inaccessible more quickly at higher temperatures.

Since warming is a prominent source of potential quantum computing errors, Green’s ability to simulate temperature fluctuations that occur when and where she wants them will also be valuable in her new computer.

The techniques developed for these projects, as well as the other expertise developed during her postdoctoral research, will be crucial as Green develops her error-creating computer and applies the power of quantum computers to studying quantum computing itself.

It Takes a Village to Do Quantum Research

Green chose to continue her research and build her new computer at JQI because it is part of a robust research community focused on quantum research. And, when constructing a new experiment from scratch, a scientist sometimes needs a friendly loan from a neighbor.

“Sometimes a big stumbling point can just be like a simple piece of equipment that's kind of specific that you just don't have, and you can't afford to take the time to buy—you know, it might not arrive for like two months,” Green says. “But having this critical mass of other people who do similar physics to you can be really helpful because they might have that piece of equipment that you need, even just to borrow it.”

Sharing ideas is also crucial. Quantum computing draws on many areas, including quantum optics, atomic and molecular physics, condensed matter physics and quantum information science. And developing quantum technology generally requires pushing the boundaries of both theory and experiment, so close collaborations between theorists and experimentalists can be invaluable. Green says local collaborations with theorists at JQI make it easier for her to work out potential stumbling blocks in advance and do experiments that push more boundaries than she could on her own.

Collaborations with researchers outside of quantum research are also valuable to Green. As the quantum computing industry matures, quantum computers are becoming useful tools for not only physics research but also other fields like chemistry and mathematics. Part of Green’s work is taking the science of manipulating atoms with lasers and translating that into a mathematical language that can be easily used to tackle research problems in unrelated fields. In her quantum computing research, Green has collaborated with chemists on simulating molecular orbitals, mathematicians who study game theory and combinatorics, and physicists investigating quantum thermodynamics.

“Working with people is my favorite part of being a physicist,” Green says. “It's always just very satisfying, when not only do you understand something, but you know that the person next to you understands something, and you both understand it, because you both brought a piece of the puzzle together. And more importantly, you had to articulate exactly what you meant to each other so the other person would understand what you were thinking. I love that opportunity.”

Green says she is particularly grateful for the chance to collaborate with the brilliant students at UMD, and as she builds her “very bad, no good, horrible quantum computer” she hopes that the students she is introducing to physics will help correct any errors she makes.

“The top piece of advice I give any student, especially those who are joining my lab, is that I am not always right and neither is anyone else who you think is more institutionally important than you,” Green says. “Kind of the mantra in my lab is, ‘If you're not contradicting me, you're not doing it right.’”

Original story by Bailey Bedford: https://jqi.umd.edu/news/new-jqi-fellow-wants-build-error-creating-quantum-computer

Grégory Moille and CMNS Dean Amitabh Varshney

Grégory Moille and CMNS Dean Amitabh Varshney