- Details

-

Published: Wednesday, March 10 2021 05:33

When NASA’s Parker Solar Probe sent back the first observations from its voyage to the Sun, scientists found signs of a wild ocean of currents and waves quite unlike the near-Earth space much closer to our planet. This ocean was spiked with what became known as switchbacks: rapid flips in the Sun’s magnetic field that reversed direction like a zig-zagging mountain road.

Scientists think piecing together the story of switchbacks is an important part of understanding the solar wind, the constant stream of charged particles that flows from the Sun. The solar wind races through the solar system, shaping a vast space weather system, which we regularly study from various vantage points around the solar system – but we still have basic questions about how the Sun initially manages to shoot out this two-million-miles-per-hour gust.

Parker Solar Probe observed switchbacks — traveling disturbances in the solar wind that caused the magnetic field to bend back on itself — an as-yet unexplained phenomenon that might help scientists uncover more information about how the solar wind is accelerated from the Sun.

Solar physicists have long known the solar wind comes in two flavors: the fast wind, which travels around 430 miles per second, and the slow wind, which travels closer to 220 miles per second. The fast wind tends to come from coronal holes, dark spots on the Sun full of open magnetic field. Slower wind emerges from parts of the Sun where open and closed magnetic fields mingle. But there is much we’ve still to learn about what drives the solar wind, and scientists suspect switchbacks – fast jets of solar material peppered throughout it – hold clues to its origins.

Since their discovery, switchbacks have sparked a flurry of studies and scientific debate as researchers try to explain how the magnetic pulses form.

“This is the scientific process in action,” said Kelly Korreck, Heliophysics program scientist at NASA Headquarters. “There are a variety of theories, and as we get more and more data to test those theories, we get closer to figuring out switchbacks and their role in the solar wind.”

Magnetic fireworks

On one side of the debate: a group of researchers who think switchbacks originate from a dramatic magnetic explosion that happens in the Sun’s atmosphere.

Signs of what we now call switchbacks were first observed by the joint NASA-European Space Agency mission Ulysses, the first spacecraft to fly over the Sun’s poles. But decades later when the data streamed down from Parker Solar Probe to the Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Lab in Laurel, Maryland, which manages the mission, scientists were surprised to find so many.

As the Sun rotates and its superheated gases churn, magnetic fields migrate around our star. Some magnetic field lines are open, like ribbons waving in the wind. Others are closed, with both ends or “footpoints” anchored in the Sun, forming loops that course with scorching hot solar material. One theory – initially proposed in 1996 based on Ulysses data – suggests switchbacks are the result of a clash between open and closed magnetic fields. An analysis published last year by scientists Justin Kasper and Len Fisk of the University of Michigan further explores the 20-year-old theory.

When an open magnetic field line brushes against a closed magnetic loop, they can reconfigure in a process called interchange reconnection – an explosive rearrangement of the magnetic fields that leads to a switchback shape. “Magnetic reconnection is a little like scissors and a soldering gun combined into one,” said Gary Zank, a solar physicist at the University of Alabama Huntsville. The open line snaps onto the closed loop, cutting free a hot burst of plasma from the loop, while “gluing” the two fields into a new configuration. That sudden snap throws an S-shaped kink into the open magnetic field line before the loop reseals – a little like, for example, the way a quick jerk of the hand will send an S-shaped wave traveling down a rope.

Other research papers have looked at how switchbacks take shape after the fireworks of reconnection. Often, this means building mathematical simulations, then comparing the computer-generated switchbacks to Parker Solar Probe data. If they’re a close match, the physics used to create the models may successfully help describe the real physics of switchbacks.

Zank led the development of the first switchbacks model. His model suggests not one, but two magnetic whips are born during reconnection: One travels down to the solar surface and one zips out into the solar wind. Like an electric wire made from a bundle of smaller wires, each magnetic loop is made of many magnetic field lines. “What happens is, each of these individual wires reconnects, so you produce a whole slew of switchbacks in a short period of time,” Zank said.

Zank and his team modelled the very first switchback Parker Solar Probe observed, on Nov. 6, 2018. This first model fit the observations well, encouraging the team to develop it further. The team’s results were published in The Astrophysical Journal on Oct. 26, 2020.

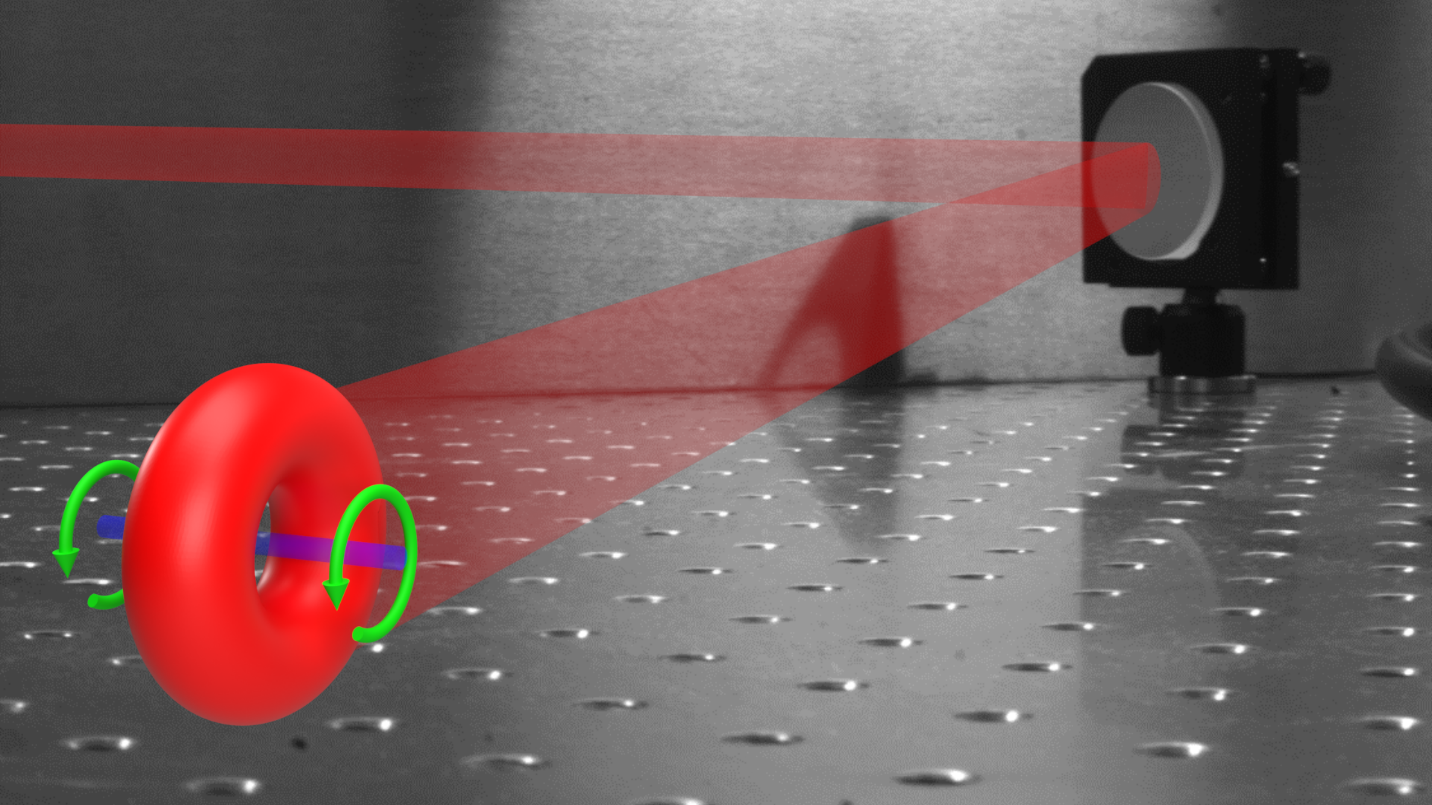

Another group of scientists, led by University of Maryland physicist James Drake, agrees on the import of interchange reconnection. But they differ when it comes to the nature of switchbacks themselves. Where others say switchbacks are a kink in a magnetic field line, Drake and his team suggest what Parker is observing is the signature of a kind of magnetic structure, called a flux rope.

In Drake’s simulations, the kink in the field didn’t travel very far before fizzling out. “Magnetic field lines are like rubber bands, they like to snap back to their original shape,” he explained. But the scientists knew the switchbacks had to be stable enough to travel out to where Parker Solar Probe could see them. On the other hand, flux ropes – which are thought to be core components of many solar eruptions – are sturdier. Picture a magnetic striped candy cane. That’s a flux rope: strips of magnetic field wrapped around a bundle of more magnetic field.

Drake and his team think flux ropes could be an important part of explaining switchbacks, since they should be stable enough to travel out to where Parker Solar Probe observed them. Their study – published in Astronomy and Astrophysics on Oct. 8, 2020 – lays the groundwork for building a flux rope-based model to describe the origins of switchbacks.

What these scientists have in common is they think magnetic reconnection can explain not only how switchbacks form, but also how the solar wind is heated and slings out from the Sun. In particular, switchbacks are linked to the slow solar wind. Each switchback shoots a gob of hot plasma into space. “So we’re asking, ‘If you add up all those bursts, can they contribute to the generation of the solar wind?’” Drake said.

Going with the flow

On the other side of the debate are scientists who believe that switchbacks form in the solar wind, as a byproduct of turbulent forces stirring it up.

Jonathan Squire, space physicist at New Zealand’s University of Otago, is one of them. Using computer simulations, he studied how small fluctuations in the solar wind evolved over time. “What we do is try and follow a small parcel of plasma as it moves outwards,” Squire said.

Each parcel of solar wind expands as it escapes the Sun, blowing up like a balloon. Waves that undulate across the Sun create tiny ripples in that plasma, ripples that gradually grow as the solar wind spreads out.

“They start out first as wiggles, but then what we see is as they grow even further, they turn into switchbacks,” Squire said. “That's why we feel it's quite a compelling idea – it just happened by itself in the model.” The team didn’t have to incorporate any guesses about new physics into their models – the switchbacks appeared based on fairly agreed-upon solar science.

Squire’s model, published on Feb. 26, 2020, suggests switchbacks form naturally as the solar wind expands into space. Parts of the solar wind that expand more rapidly, he predicts, should also have more switchbacks – a prediction already testable with the latest Parker dataset.

Other researchers agree that switchbacks begin in the solar wind, but suspect they form when fast and slow streams of solar wind rub against one another. One October 2020 study, led by Dave Ruffolo at Mahidol University in Bangkok, Thailand, outlined this idea.

Bill Matthaeus, a co-author on the paper and space physicist at the University of Delaware in Newark, points to the shearing at the boundary between fast and slow streams. This shearing between fast and slow creates characteristic swirls seen all over in nature, like the eddies that form as river water flows around a rock. Their models suggest that these swirls ultimately become switchbacks, curling the magnetic field lines back on themselves.

But the swirls don’t form immediately – the solar wind has to be moving pretty fast before it can bend its otherwise rigid magnetic field lines. The solar wind reaches this speed about 8.5 million miles from the Sun. Mattheaus’ key prediction is that when Parker gets significantly closer to the Sun than that – which should happen during its next close pass 6.5 million miles from the Sun, on April 29, 2021 – the switchbacks should disappear.

“If this is the origin, then as Parker moves into the lower corona this shearing can't happen,” Mattheaus said. “So, the switchbacks caused by the phenomenon we're describing should go away.”

One aspect of switchbacks that these solar wind models haven’t yet successfully simulated is the fact that they tend to be stronger when they twist in a particular direction – the same direction of the Sun’s rotation. However, both simulations were created with a Sun that was still, not rotating, which may make the difference. For these modelers, incorporating the actual rotation of the Sun is the next step.

Twisting in the wind

Finally, some scientists think switchbacks stem from both processes, starting with reconnection or footpoint motion at the Sun but only growing into their final shape once they get out into the solar wind. A paper published today by Nathan Schwadron and David McComas, space physicists at the University of New Hampshire and Princeton University, respectively, adopts this approach, arguing that switchbacks form when streams of fast and slow solar wind realign at their roots.

After this realignment fast wind ends up “behind” slow wind, on the same magnetic field line. (Imagine a group of joggers on a race track, Olympic sprinters at their heels.) This could happen in any case where slow and fast wind meet, but most notably at the boundaries of coronal holes, where fast solar wind is born. As coronal holes migrate across the Sun, scooting underneath streams of slower solar wind, the footpoint from the slow solar wind plugs into a source of fast wind. Fast solar wind races after the slower stream ahead of it. Eventually the fast wind overtakes the slower wind, inverting the magnetic field line and forming a switchback.

Schwadron thinks the motion of coronal holes and of solar wind sources across the Sun is also a key puzzle piece. Reconnection at the leading edge of coronal holes, he suggests, could explain why switchbacks tend to “zig” in a way that’s aligned with the Sun’s rotation.

“The fact that these are oriented in this particular way is telling us something very fundamental,” Schwadron said.

Though it starts with the Sun, Schwadron and McComas think those reconnecting streams only become switchbacks within the solar wind, where the Sun’s magnetic field lines are flexible enough to double-back on themselves.

As Parker Solar Probe swoops closer and closer to the Sun, scientists will eagerly look for clues that will support – or debunk – their theories. “There are different ideas floating around,” Zank said. “Eventually something will pan out.”

Parker Solar Probe is part of NASA’s Living With a Star program to explore aspects of the Sun–Earth system that directly affect life and society. The Living With a Star flight program is managed by the agency’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland, for NASA’s Science Mission Directorate in Washington, D.C. The Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory implements the mission for NASA. Scientific instrumentation is provided by teams led by the Naval Research Laboratory, Princeton University, the University of California, Berkeley, and the University of Michigan.

This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it. & This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, Greenbelt, Md.

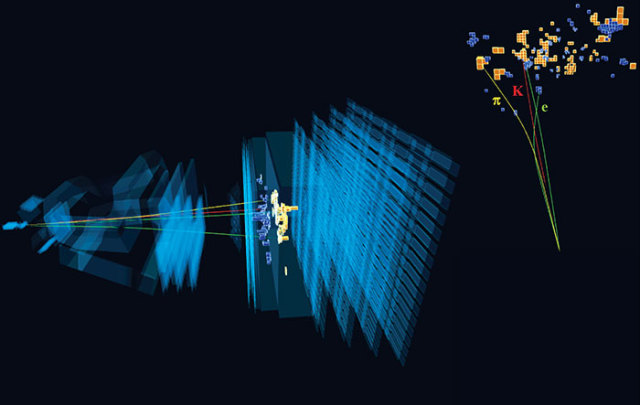

The decay of a B0 meson into a K*0 and an electron–positron pair in the LHCb detector, which is used for a sensitive test of lepton universality in the Standard Model. Credit: CERN Large Hadron Collider beauty (LHCb) experiment at CERN raises the tantalizing prospect of new physics beyond the Standard Model picture.

The decay of a B0 meson into a K*0 and an electron–positron pair in the LHCb detector, which is used for a sensitive test of lepton universality in the Standard Model. Credit: CERN Large Hadron Collider beauty (LHCb) experiment at CERN raises the tantalizing prospect of new physics beyond the Standard Model picture.