- Details

-

Category: Research News

-

Published: Tuesday, August 04 2020 05:33

Flashlight beams don’t clash together like lightsabers because individual units of light—photons—generally don’t interact with each other. Two beams don’t even flicker when they cross paths.

But by using matter as an intermediary, scientists have unlocked a rich world of photon interactions. In these early days of exploring the resulting possibilities, researchers are tackling topics like producing indistinguishable single photons and investigating how even just three photons form into basic molecules of light. The ability to harness these exotic behaviors of light is expected to lead to advances in areas such as quantum computing and precision measurement.

In a paper recently published in Physical Review Research, Adjunct Associate Professor Alexey Gorshkov, Joint Quantum Institute (JQI) postdoctoral researcher Przemyslaw Bienias, and their colleagues describe an experiment that investigates how to extract a train of single photons from a laser packed with many photons.

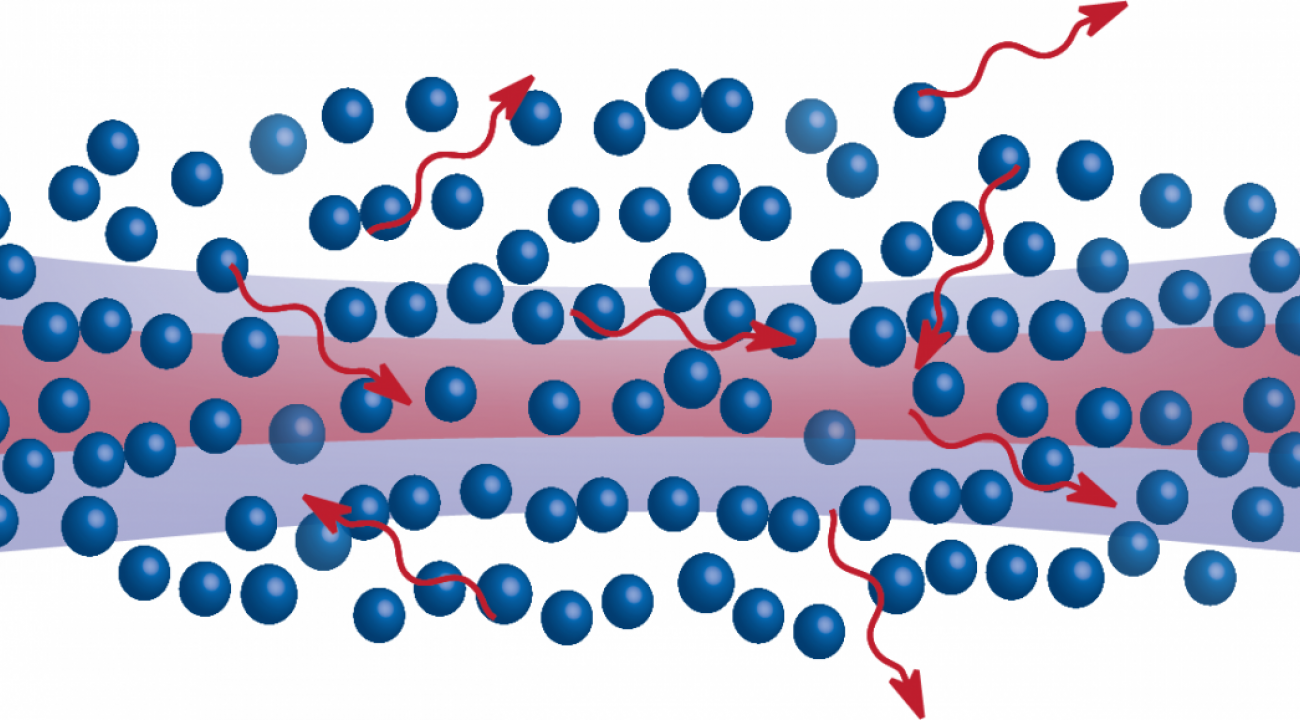

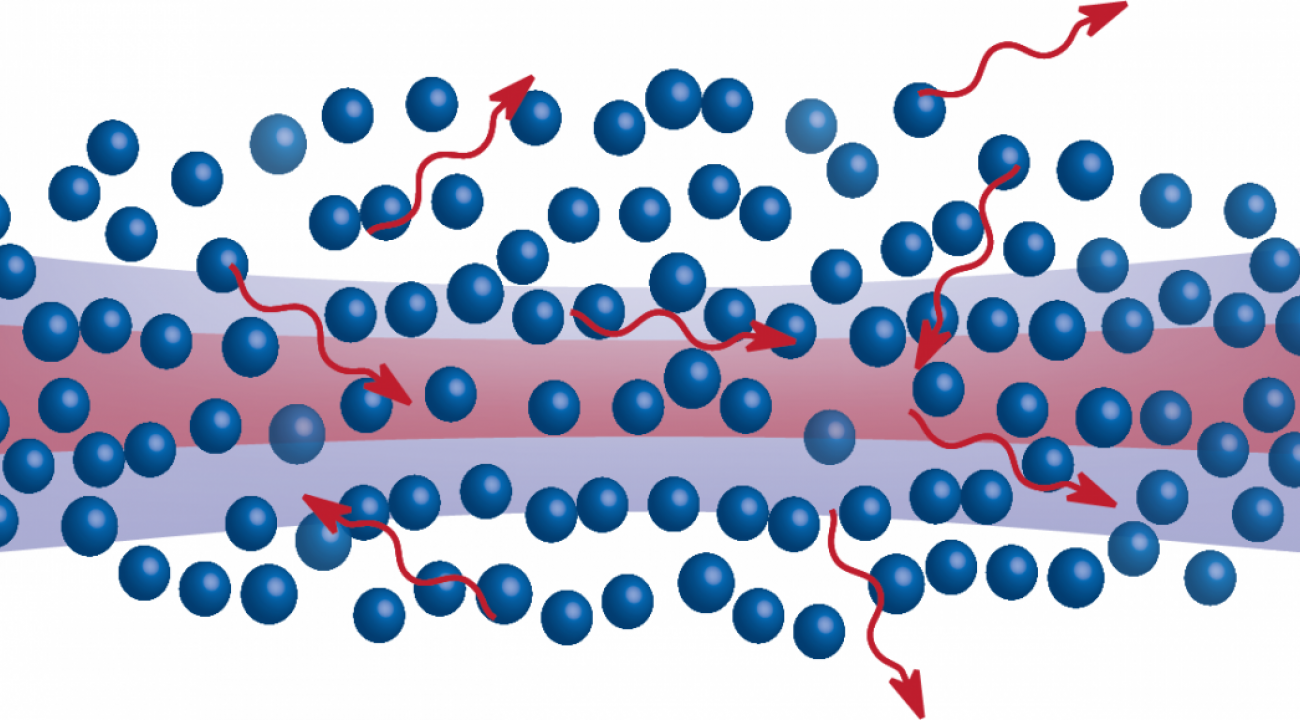

In the experiment, the researchers examined how photons in a laser beam can interact through atomic intermediaries so that most photons are dissipated—scattered out of the beam—and only a single photon is transmitted at a time. They also developed an improved model that makes better predictions for more intense levels of light than previous research focused on (greater intensity is expected to be required for practical applications). The new results reveal details about the work to be done to conquer the complexities of interacting photons. A cloud of Rydberg atoms can scatter most light to whittle a laser down to train of individual photons. But photons can get re-absorbed within the larger control beam making things more complicated. (Credit: Przemyslaw Bienias, University of Maryland)

A cloud of Rydberg atoms can scatter most light to whittle a laser down to train of individual photons. But photons can get re-absorbed within the larger control beam making things more complicated. (Credit: Przemyslaw Bienias, University of Maryland)

“Until recently, it was basically too difficult to study anything other than a few of these interacting photons because even when we have two or three things get extremely complicated,” says Gorshkov, whi is also a physicist at the National Institute of Standards and Technology and Fellow of the Joint Center for Quantum Information and Computer Science. “The hope with this experiment was that dissipation would somehow simplify the problem, and it sort of did.”

Trains, Blockades and Water Slides

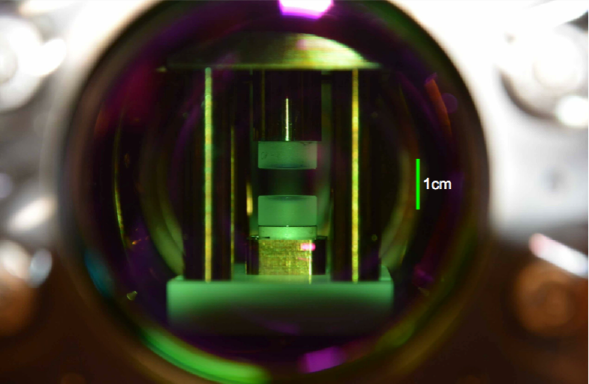

To create the interactions, the researchers needed atoms that are sensitive to the electromagnetic influence of individual photons. Counterintuitively, the right tool for the job is a cloud of electrically neutral atoms. But not just any neutral atoms; these specific atoms—known as Rydberg atoms—have an electron with so much energy that it stays far from the center of the atom.

The atoms become photon intermediaries when these electrons are pushed to their extreme, remaining just barely tethered to the atom. With the lone, negatively charged electron so far out, the central electrons and protons are left contributing a counterbalancing positive charge. And when stretched out, these opposite charges make the atom sensitive to the influence of passing photons and other atoms. In the experiment, the interactions between these sensitive atoms and photons is tailored to turn a laser beam that is packed with photons into a well-spaced train.

The cloud of Rydberg atoms is kind of like a lifeguard at a water park. Instead of children rushing down a slide dangerously close together, only one is allowed to pass at a time. The lifeguard ensures the kids go down the slide as a steady, evenly spaced train and not in a crowded rush.

Unlike a lifeguard, the Rydberg atoms can’t keep the photons waiting in line. Instead they let one through and turn away the rest for a while. The interactions in the cloud of atoms form a blockade around each transmitted photon that scatters other photons aside, ensuring its solitary journey.

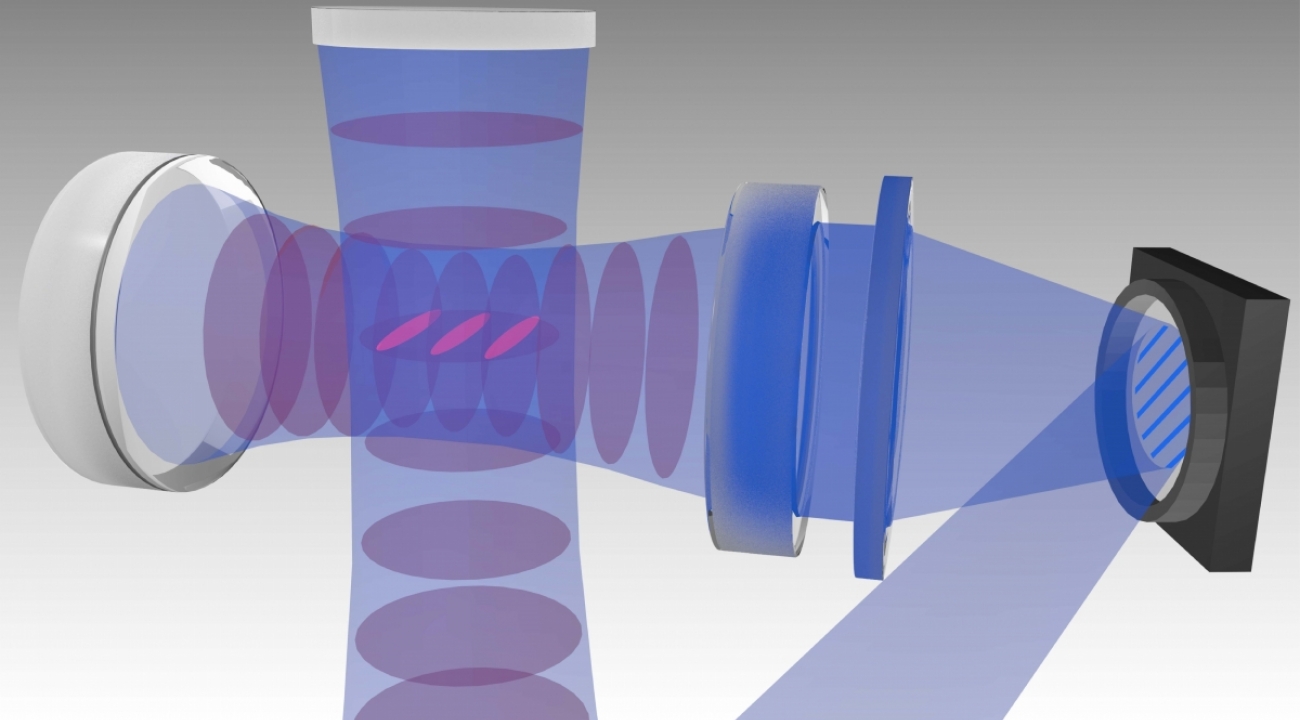

To achieve the effect, the researchers used Rydberg atoms and a pair of lasers to orchestrate a quantum mechanical balancing act. They selected the frequency of the first laser so that its photons would be absorbed by the atoms and scattered in a new direction. But this is the laser that is whittled down into the photon train, and they needed a way to let individual photons through.

That’s were the second laser comes in. It creates another possible photon absorption that quantum mechanically interferes with the first and allows a single photon to pass unabsorbed. When that single photon gets through, it disturbs the state of the nearby atoms, upsetting the delicate balance achieved with the two lasers and blocking the passage of any photons crowding too closely behind.

Ideally, if this process is efficient and the stream of photons is steady enough, it should produce a stream of individual photons each following just behind the blockade of the previous. But if the laser is not intense enough, it is like a slow day at the waterpark, when there is not always a kid eagerly awaiting their turn. In the new experiment, the researchers focused on what happens when they crowed many photons into the beam.

Model (Photon) Trains

Gorshkov and Bienias’s colleagues performed the experiment, and the team compared their results to two previous models of the blockade effect. Their measurements of the transmitted light matched the models when the number of photons was low, but as the researchers pushed the intensity to higher levels, the results and the models’ predictions started looking very different. It looked like something was building up over time and interfering with the predicted, desired formation of well-defined photon trains.

The team determined that the models failed to account for an important detail: the knock-on effects of the scattered photons. Just because those photons weren’t transmitted, doesn’t mean they could be ignored. The team suspected the models were being thrown off by some of the scattered light interacting with Rydberg atoms outside of the laser beam. These additional interactions would put the atoms into new states, which the scientists call pollutants, that would interfere with the efficient creation of a single photon train.

The researchers modified one of their models to capture the important effects of the pollutants without keeping track of every interaction in the larger cloud of atoms. While this simplified model is called a “toy model,” it is really a practical tool that will help researchers push the technique to greater heights in their larger effort to understand photon interactions. The model helped the researchers explain the behavior of the transmitted light that the older models failed to capture. It also provides a useful way to think about the physics that is preventing an ideal single photon train and might be useful in judging how effectively future experiments prevent the undesirable affects—perhaps by using cloud of atoms with different shapes.

“We are quite optimistic when it comes to removing the pollutants or trying to create less of them,” says Bienias. “It will be more experimentally challenging, but we believe it is possible.”

Original story by Bailey Bedford: https://jqi.umd.edu/news/scientists-see-train-photons-new-light

In addition to Bienias and Gorshkov, James Douglas, a Co-founder at MEETOPTICS; Asaf Paris-Mandoki, a physics researcher at Instituto de Física, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México; JQI postdoctoral researcher Paraj Titum; Ivan Mirgorodskiy; Christoph Tresp, a research and development employee at TOPTICA Photonics; Emil Zeuthen, a physics professor at the Niels Bohr Institute; Michael J. Gullans, a former JQI postdoctoral researcher and current associate scholar at Princeton University; Marco Manzoni, a data scientist at Big Blue Analytics; Sebastian Hofferberth, a professor of physics at the University of Southern Denmark; and Darrick Chang, a professor at the Institut de Ciencies Fotoniques, were also co-authors of the paper.

"Photon propagation through dissipative Rydberg media at large input rates," Przemyslaw Bienias, James Douglas, Asaf Paris-Mandoki, Paraj Titum, Ivan Mirgorodskiy, Christoph Tresp, Emil Zeuthen, Michael J. Gullans, Marco Manzoni, Sebastian Hofferberth, Darrick Chang, Alexey V. Gorshkov, Phys. Rev. Research, 2, 033049 (2020)