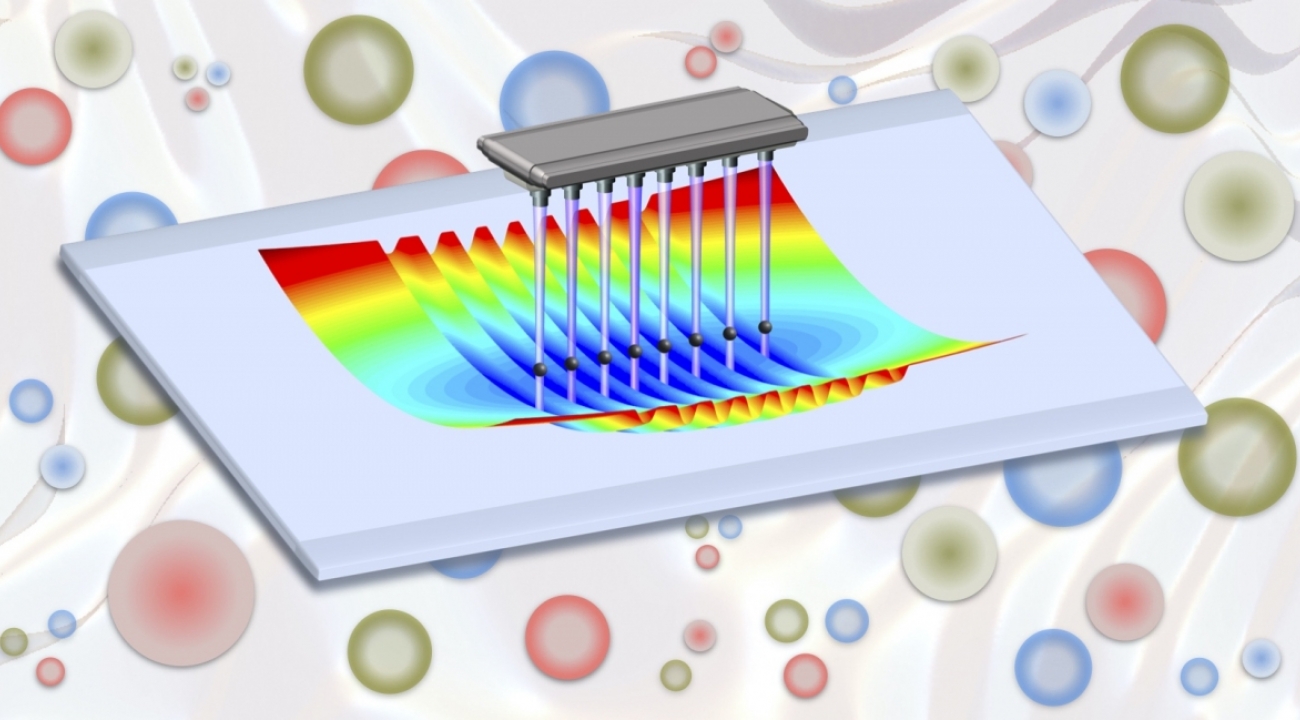

In nuclear physics, like much of science, detailed theories alone aren’t always enough to unlock solid predictions. There are often too many pieces, interacting in complex ways, for researchers to follow the logic of a theory through to its end. It’s one reason there are still so many mysteries in nature, including how the universe’s basic building blocks coalesce and form stars and galaxies. The same is true in high-energy experiments, in which particles like protons smash together at incredible speeds to create extreme conditions similar to those just after the Big Bang. Trapped ion quantum simulators may soon offer new means to explore the properties of matter emerging from complex interactions among quarks, gluons and the other fundamental building blocks of nature. (Credit: A. Shaw and Z. Davoudi/University of Maryland)

Trapped ion quantum simulators may soon offer new means to explore the properties of matter emerging from complex interactions among quarks, gluons and the other fundamental building blocks of nature. (Credit: A. Shaw and Z. Davoudi/University of Maryland)

Fortunately, scientists can often wield simulations to cut through the intricacies. A simulation represents the important aspects of one system—such as a plane, a town’s traffic flow or an atom—as part of another, more accessible system (like a computer program or a scale model). Researchers have used their creativity to make simulations cheaper, quicker or easier to work with than the formidable subjects they investigate—like proton collisions or black holes.

Simulations go beyond a matter of convenience; they are essential for tackling cases that are both too difficult to directly observe in experiments and too complex for scientists to tease out every logical conclusion from basic principles. Diverse research breakthroughs—from modeling the complex interactions of the molecules behind life to predicting the experimental signatures that ultimately allowed the identification of the Higgs boson—have resulted from the ingenious use of simulations.

But conventional simulations only get you so far. In many cases, a simulation requires so many computations that the best computers ever built can’t make meaningful progress—not even if you are willing to wait your entire life.

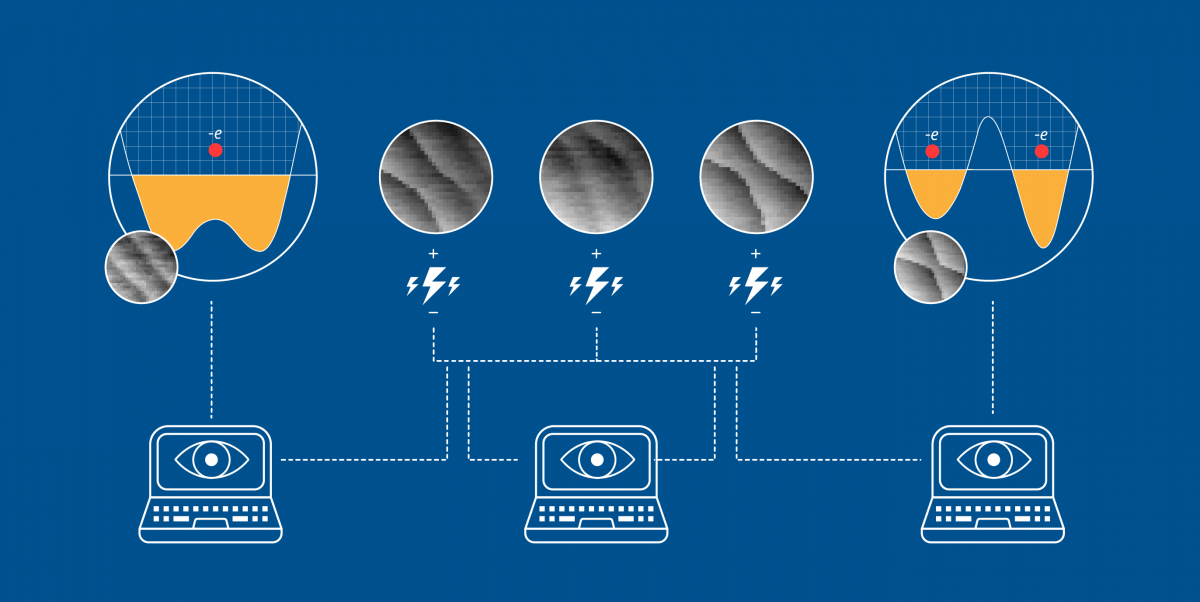

Now, quantum simulators (which exploit quantum effects like superposition and entanglement) promise to bring their power to bear on many problems that have refused to yield to simulations built atop classical computers—including problems in nuclear physics. But to run any simulation, quantum or otherwise, scientists must first determine how to faithfully represent their system of interest in their simulator. They must create a map between the two.

Assistant professor Zohreh Davoudi, a computational nuclear physicist, is collaborating with researchers at the Joint Quantum Institute to explore how quantum simulations might aid nuclear physicists. They are working to create some of the first maps between the theories that describe the underpinnings of nuclear physics and the early quantum simulators and quantum computers being put together in labs.

“It seems like we are at the verge of going into the next phase of computing that takes advantage of quantum mechanics,” says Davoudi. “And if nuclear scientists don't get into this field now—if we don't start to move our problems into such quantum hardware, we might not be able to catch up later because quantum computing is evolving very fast.”

Davoudi and several colleagues, including Chris Monroe and Mohammad Hafezi, designed their approach to making maps with an eye toward compatibility with the quantum technologies on the horizon. In a new paper published April 8, 2020 in the journal Physical Review Research, they describe their new method and how it creates new simulation opportunities for researchers to explore.

“It is not yet clear exactly where quantum computers will be usefully applied,” says Monroe, who is also a professor of physics at UMD and co-founder of the quantum computing startup IonQ. “One strategy is to deploy them on problems that are based in quantum physics. There are many approaches in electronic structure and nuclear physics that are so taxing to normal computers that quantum computers may be a way forward.”

Patterns and Control

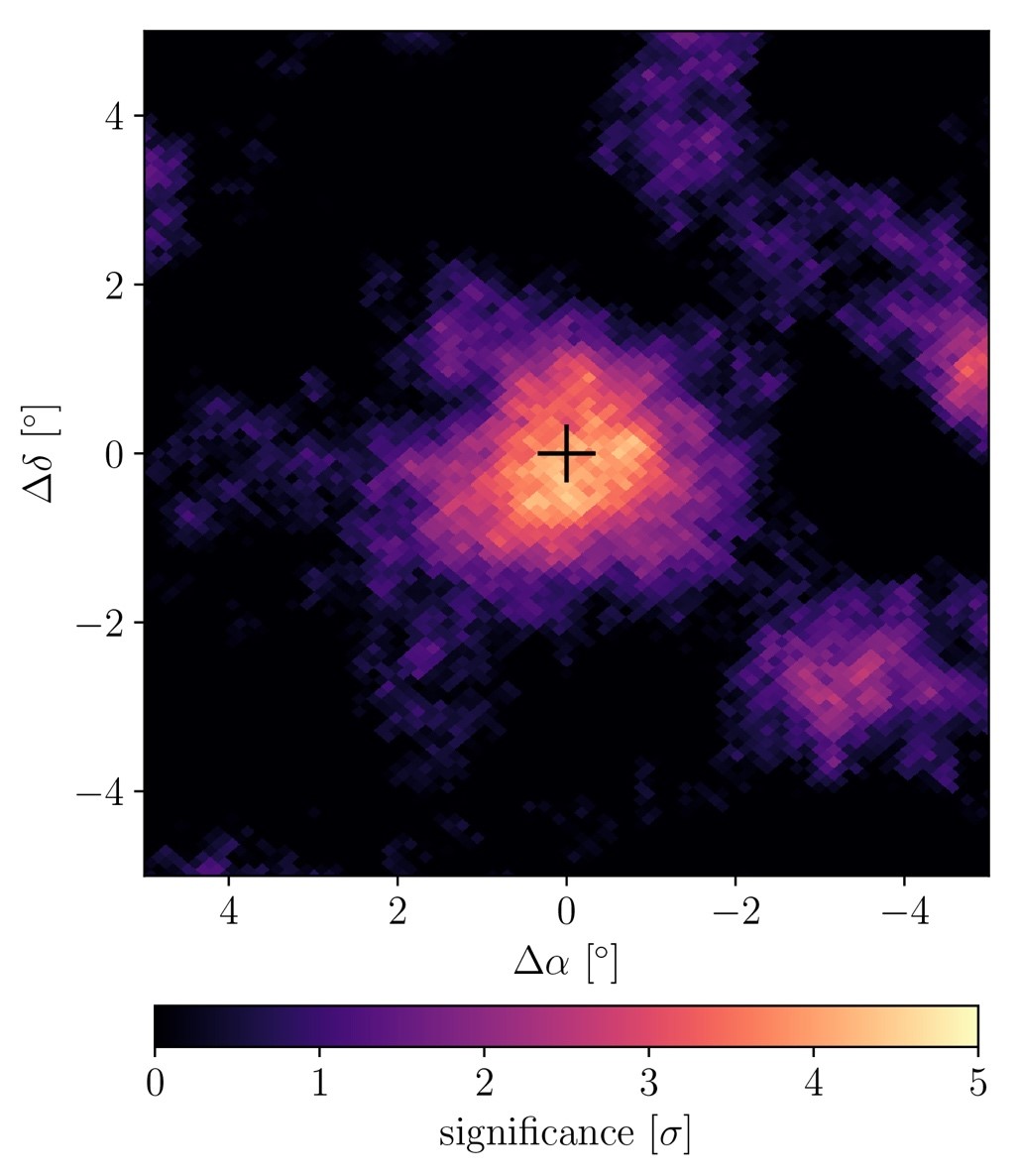

As a first target, the team set their sights on lattice gauge theories. Gauge theories describe a wide variety of physics, including the intricate dance of quarks and gluons—the fundamental particles in nuclear physics. Lattice versions of gauge theories simplify calculations by restricting all the particles and their interactions to an orderly grid, like pieces on a chessboard.

Even with this simplification, modern computers can still choke when simulating dense clumps of matter or when tracking how matter changes over time. The team believes that quantum computers might overcome these limitations and eventually simulate more challenging types of gauge theories—such as quantum chromodynamics, which describes the strong interactions that bind quarks and gluons into protons and neutrons and hold them together as atomic nuclei.

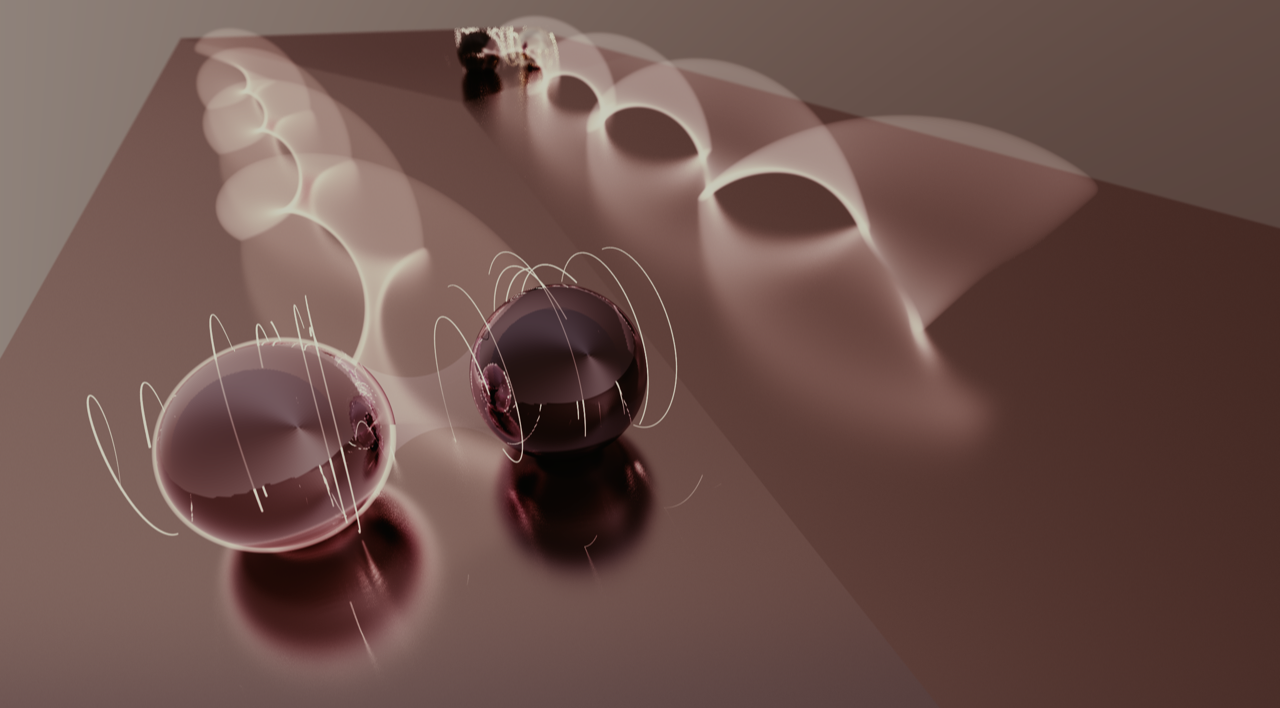

Davoudi and her colleagues chose trapped atomic ions—the specialty of Monroe—as the physical system for performing their simulation. In these systems, ions, which are electrically charged atoms, hover, each trapped by a surrounding electric or magnetic field. Scientists can design these fields to arrange the ions in various patterns that can be used to store and transfer information. For this proposal, the team focused on ions organized into a straight line.

Researchers use lasers to control each ion and its interactions with neighbors—an essential ability when creating a useful simulation. The ions are much more accessible than the smaller particles that intrigue Davoudi. Nuclear physicists can only dream of achieving the same level of control over the interactions at the hearts of atoms.

“Take a problem at the femtometer scale and expand it to micron scale—that dramatically increases our level of control,” says Hafezi, who is also an associate professor in the Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering and the Department of Physics at UMD. “Imagine you were supposed to dissect an ant. Now the ant is stretched to the distance between Boston and Los Angeles.”

While designing their map-making method, the team looked at what can be done with off-the-shelf lasers. They realized that current technology allows ion trappers to set up lasers in a new, efficient way that allows for simultaneous control of three different spin interactions for each ion.

“Trapped-ion systems come with a toolbox to simulate these problems,” says Hafezi. “Their amazing feature is that sometimes you can go back and design more tools and add it to the box.”

With this opportunity in mind, the researchers developed a procedure for producing maps with two desirable features. First, the maps maximize how faithfully the ion-trap simulation matches a desired lattice gauge theory. Second, they minimize the errors that occur during the simulation.

In the paper, the researchers describe how this approach might allow a one-dimensional string of ions to simulate a few simple lattice gauge theories, not only in one dimension but also higher dimensions. With this approach, the behavior of ion spins can be tailored and mapped to a variety of phenomena that can be described by lattice gauge theories, such as the generation of matter and antimatter out of a vacuum.

“As a nuclear theorist, I am excited to work further with theorists and experimentalists with expertise in atomic, molecular, and optical physics and in ion-trap technology to solve more complex problems,” says Davoudi. “I explained the uniqueness of my problem and my system, and they explained the features and capabilities of their system, then we brainstormed ideas on how we can do this mapping.”

Monroe points out that “this is exactly what is needed for the future of quantum computing. This ‘co-design’ of devices tailored for specific applications is what makes the field fresh and exciting.”

Analog vs. Digital

The simulations proposed by Davoudi and her colleagues are examples of analog simulations, since they directly represent elements and interactions in one system with those of another system. Generally, analog simulators must be designed for a particular problem or set of problems. This makes them less versatile than digital simulators, which have an established set of discrete building blocks that can be put together to simulate nearly anything given enough time and resources.

The versatility of digital simulations has been world-altering, but a well-designed analog system is often less complex than its digital counterpart. Carefully designed quantum analog simulations might deliver results for certain problems before quantum computers can reliably perform digital simulations. This is similar to just using a wind tunnel instead of programming a computer to model the way the wind buffets everything from a goose to an experimental fighter plane.

Monroe’s team, in collaboration with coauthor Guido Pagano, a former JQI postdoctoral researcher who is now an assistant professor at Rice University, is working to implement the new analog approach within the next couple of years. The completed system should be able to simulate a variety of lattice gauge theories.

The authors say that this research is only the beginning of a longer road. Since lattice gauge theories are described in mathematically similar ways to other quantum systems, the researchers are optimistic that their proposal will find uses beyond nuclear physics, such as in condensed matter physics and materials science. Davoudi is also working to develop digital quantum simulation proposals with Monroe and Norbert Linke, another JQI Fellow. She hopes that the two projects will reveal the advantages and disadvantages of each approach and provide insight into how researchers can tackle nuclear physics problems with the full might of quantum computing.

“We want to eventually simulate theories of a more complex nature and in particular quantum chromodynamics that is responsible for the strong force in nature,” says Davoudi. “But that might require thinking even more outside the box.”

Original story by Bailey Bedford

In addition to Davoudi, Hafezi and Monroe, co-authors of the paper include former JQI postdoctoral researcher and current assistant professor at Rice University Guido Pagano; JQI graduate student Alireza Seif, and UMD Physics graduate student Andrew Shaw.

E. Edwards, IQUIST

E. Edwards, IQUIST