Malcolm Maas Named 2025-26 Churchill Scholar

- Details

- Category: Department News

- Published: Wednesday, January 29 2025 01:40

University of Maryland senior Malcolm Maas has been awarded a 2025-26 Churchill Scholarship, joining only 15 other science, engineering and mathematics students nationwide in winning the prestigious honor.

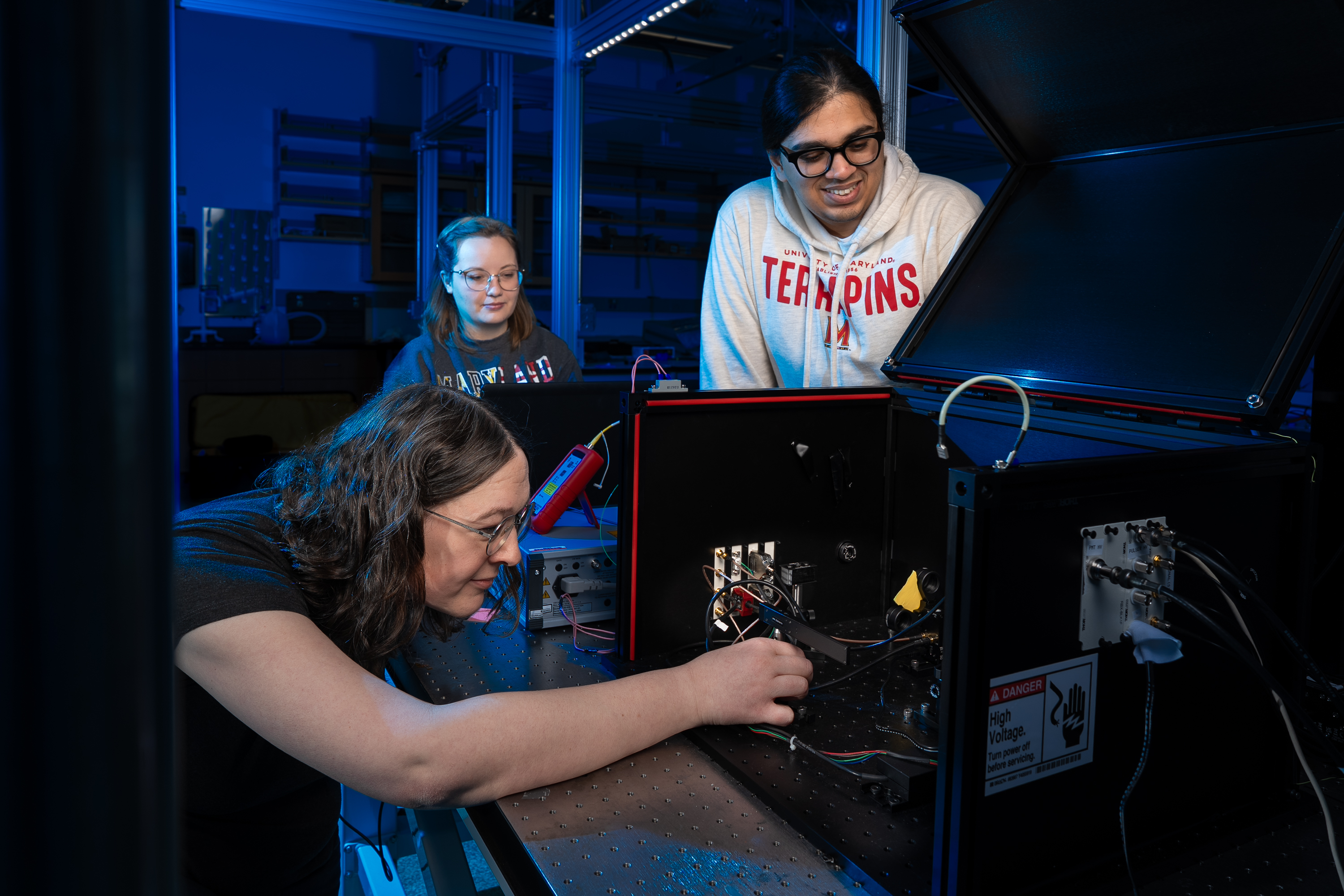

“We could not be prouder of how Malcolm Maas represents the University of Maryland to the world,” said Amitabh Varshney, dean of UMD’s College of Computer, Mathematical, and Natural Sciences. “Malcolm is a phenomenal student researcher who is driven to understand complex world problems like climate change and provide innovative solutions to them.” Malcolm Maas. Photo courtesy of same.

Malcolm Maas. Photo courtesy of same.

Maas, who plans to graduate in three years with bachelor’s degrees in atmospheric and oceanic science (AOSC) and physics, will receive full funding to pursue a one-year master’s degree at the University of Cambridge’s Churchill College in the United Kingdom. The scholarship covers full tuition, a competitive stipend, travel costs and the chance to apply for a special research grant.

Maas plans to pursue a Master of Philosophy degree in mathematics.

“I feel incredibly honored to have received this scholarship, and I’m very grateful to everyone who has supported me on my way here,” Maas said. “I’m excited for the opportunity to explore atmospheric dynamics further and to experience Cambridge next year.”

A total of 127 nominations this year came from 82 participating institutions. Ten UMD students have been nominated in the past seven years—and nine of them have been named Churchill Scholars.

“The University of Maryland’s remarkable success in racking up Churchill Scholarships testifies to the excellence of the research opportunities and mentorship our undergraduates receive,” said Francis DuVinage, director of UMD’s National Scholarships Office. “Malcolm Maas’ record of accomplishment as a third-year senior puts him in a class by himself.”

Since 2022, Maas has been working with AOSC Associate Professor Jonathan Poterjoy on fundamental challenges associated with environmental prediction and validation of atmospheric modeling systems. Specifically, he is quantifying the degree to which commonly used data assimilation methods shift models away from physically plausible solutions due to commonly adopted but incorrect assumptions. Maas presented their work in January 2025 at the American Meteorological Society Annual Meeting.

“Malcolm initiated our research collaboration on his own and I fully expect him to draft a first-author paper that we submit for publication this year,” Poterjoy said. “I feel that Malcolm can succeed in virtually any field, and I am pleased to see that he chose a research career in atmospheric science where his talents can have broad human impact.”

Maas’ research interests and experiences extend beyond his work with Poterjoy and currently range from weather time scales to climate time scales.

In summer 2024, Maas interned at the University of Chicago with Geophysical Sciences Professor Tiffany Shaw, where he assessed extreme heat and atmospheric circulation trends associated with Arctic sea ice loss in climate models and observational datasets. He presented this work at the American Geophysical Union’s Annual Meeting in 2024.

In summer 2023, Maas participated in the undergraduate summer intern program at the Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory and worked on a project with Kostas Tsigaridis, a research scientist at Columbia University and the NASA Goddard Institute for Space Studies. Maas used a large dataset of Earth system model simulations to explore the effects of volcanoes on climate and atmospheric sulfur. He used machine learning to develop a tool that estimates where unidentified historical eruptions happened based on ice core data. Maas presented this work at the European Geosciences Union’s General Assembly in 2024 in Austria.

When Maas arrived at UMD in 2022, he joined a group of AOSC students installing and managing a micronet—a small-scale network of weather sensors—across the university’s campus. Five weather stations now provide minute-by-minute updates on the temperature, wind speed, pressure, dew point and rain rate on campus. Maas helped create the data collection system and user-friendly graphs to visualize the data, which are displayed on the UMD Weather website.

When the university and the Maryland Department of Emergency Management installed their first weather tower as part of the Maryland Mesonet in 2023, they asked Maas to quickly adapt his micronet visualization tools to work with the mesonet data. The 23 towers operational around the state—with more than 70 planned—help to advance localized weather prediction and ensure the safety of Maryland's residents and visitors.

For his Gemstone honors research project, Maas and 10 teammates have been working with UMD Mechanical Engineering Professor Johan Larsson to optimize the shape of marine propellers.

In high school, Maas helped build the first global tornado climatology database. He gathered and processed historical data for over 100,000 tornadoes that occurred around the world. The project’s website raked in 160,000 page views during its first year, and the work was published in the Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society in 2024.

Outside of class, Maas plays the pipe organ, represents the Ellicott Community on the Student Government Association, tutors with the Society of Physics Students and is a member of the Ballooning Club. He received a Barry M. Goldwater Scholarship, National Merit Scholarship, President’s Scholarship and the Department of Physics’ Angelo Bardasis Scholarship.

After his time at the University of Cambridge, Maas plans to pursue a Ph.D. in atmospheric science.