Remembering and Giving Back

- Details

- Category: Department News

- Published: Wednesday, February 04 2026 01:40

It’s been more than 30 years, but Jeff Saul (M.S. ’91, Ph.D. ’98, physics) still remembers the week that changed his life.

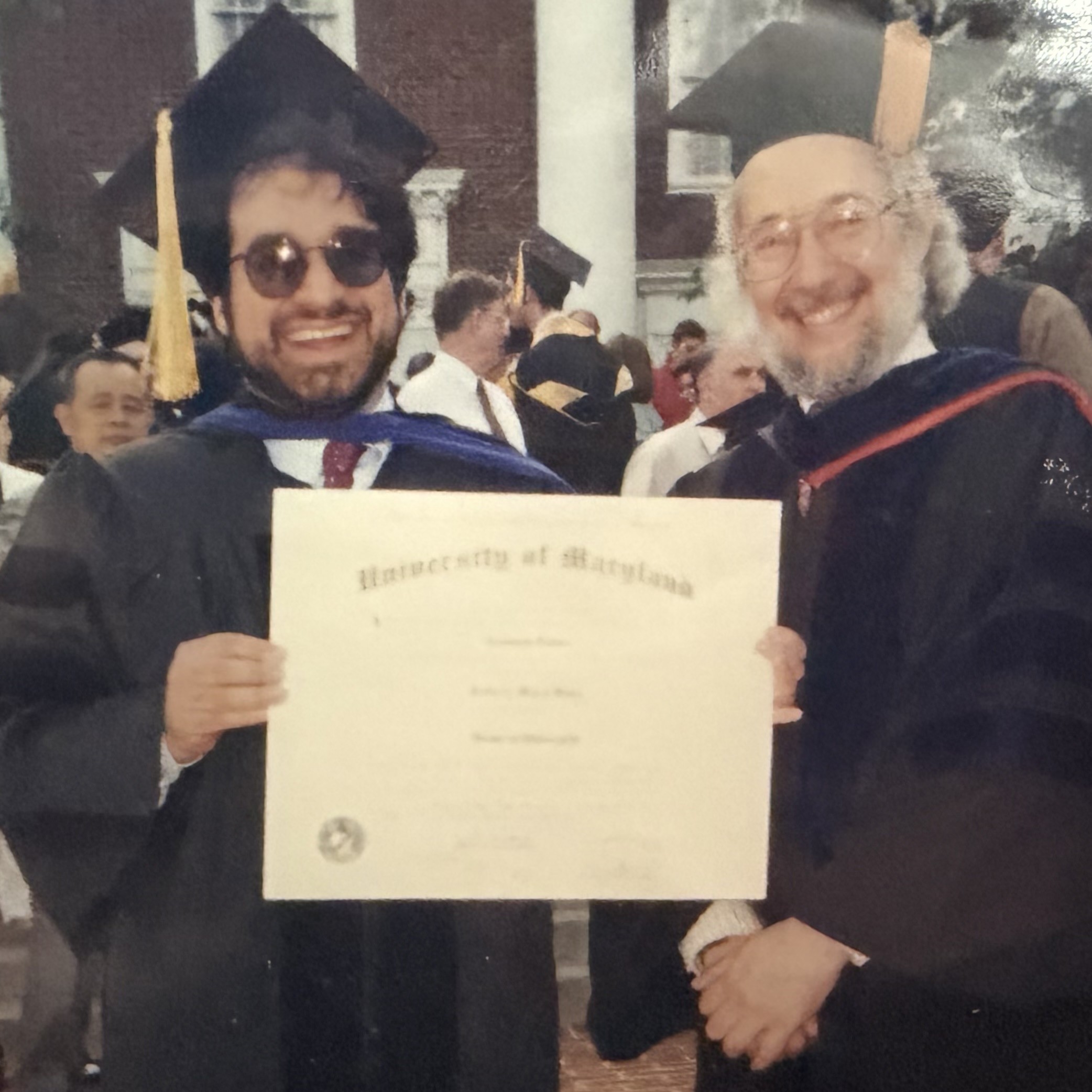

“I guess I must have been in the right place at the right time, because that week started with Joe Redish becoming my advisor, then, the same week, I had my first date with Joy—who’s now my wife—and I got my first teaching job,” Saul recalled. “That week changed everything.” Jeff Saul and Joe Redish

Jeff Saul and Joe Redish

At the time, Saul was a physics graduate student at the University of Maryland, looking forward to a career teaching college-level physics. The late Physics Professor Joe Redish, a nuclear theorist who became an internationally recognized expert in physics education research, became Saul’s mentor and friend and made him part of the new Maryland Physics Education Research Group (PERG).

“It was great to work for Joe. It was exciting and fun,” Saul recalled. “For me, it was the first time I was working in a physics lab where everything just sort of clicked.”

In their work, Saul and Redish and the rest of the founding Maryland PERG group members (Richard Steinberg, Michael Wittmann, Mel Sabella, and Bao Lei) conducted research on students’ physics learning, developed new assessment strategies, and explored innovative, activity-based approaches to teaching college-level physics. As they developed strategies to make physics education less lecture-driven and more interactive, Saul and Redish operated on the same wavelength—in more ways than one.

“If you saw the two of them together, you could see the connection,” recalled Saul’s wife, Joy Watnik-Saul. “They both had the beards, and they both had the round glasses. And they both wore that same kind of fedora-type hat. So, people would sometimes call Jeff a ‘Mini Joe.’ Joe was just a really important part of Jeff’s life and his whole career.”

For Saul, Redish’s mentorship and their work in physics education research became the inspiration for a decades-long career as a teacher, advocate, innovator in physics and STEM education, and physics faculty member at the University of Central Florida, Florida International University and the University of New Mexico. Now retired, Saul is committed to paying that life-changing UMD physics experience forward.

“I knew I wanted to make a contribution that would last longer than me,” Saul explained. “I want physics education research to continue at Maryland, and I want Maryland to continue working at making physics more fun and more accessible and helping students get more out of it.”

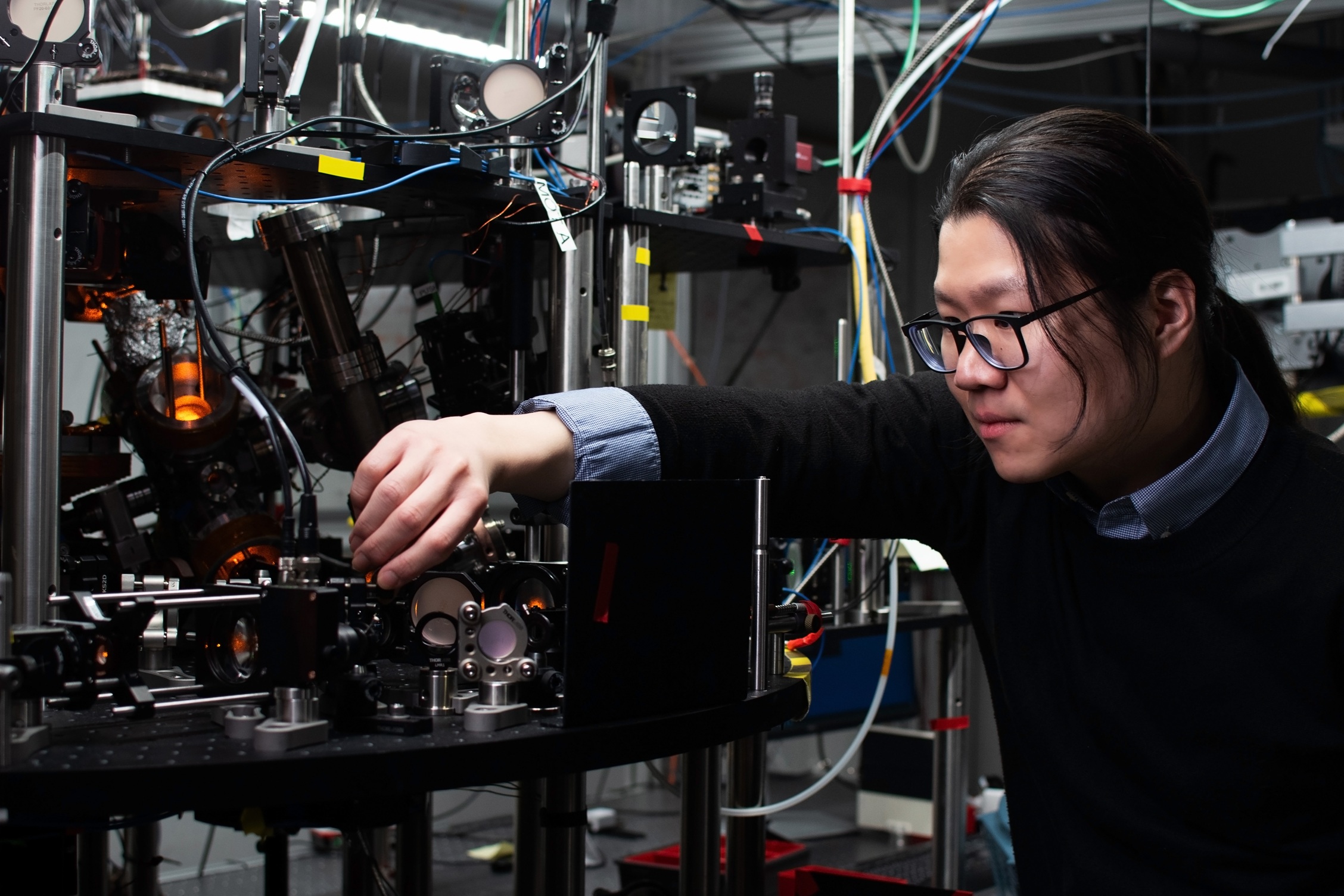

Now, Saul and his wife are doing their part by making a planned gift to Forward: The University of Maryland Campaign for the Fearless, a $2.5 billion initiative that officially launched in November 2025 to accelerate advances in research, education and science. Joy Watnik-Saul and Jeff Saul

Joy Watnik-Saul and Jeff Saul

“Joe Redish was one of the pioneers of physics education research – the recognition that if we want to improve the teaching of physics, it needs to be done by physicists, treating it as a science. This has since broadened throughout the sciences as discipline-based science education research,” Physics Chair Steven Rolston explained. “This gift from Jeff and Joy emphasizes the outsized impact of Joe’s work and helps continue the tradition here at UMD.”

The Sauls’ generous gift will establish the Dr. Jeff Saul and Joy Watnik-Saul Endowed Distinguished Graduate Fellowship in Physics.

“It’s a fellowship for graduate students doing physics education research,” Saul explained, “and the fact that there's a fellowship for that helps increase the prestige of the field, and it helps attract good graduate students to continue to work in the field.”

To support physics undergraduates interested in physics education, they will also establish the Dr. Jeff Saul and Joy Watnik-Saul Endowed Undergraduate Student Support Fund in Physics.

“The undergraduate scholarship is for a student doing physics education research,” Saul said. “The idea is to get students interested in this field and keep them going forward.”

The Sauls’ gift also includes a contribution to name a collaboration room in the Physical Sciences Complex in memory of Redish.

“A research group really should have its own space and its own conference room where they can get together and talk, and I remember that being part of an active group was a big part of being at Maryland, working on a lot of different things, sharing ideas and really being a team,” Saul said. “And I thought, what a great way to memorialize Joe as well.”

The Sauls’ commitment is also part of the Bequest Legacy Challenge, an incentive program that provides an immediate cash match for donors who document new or increased planned giving commitments to the College of Computer, Mathematical, and Natural Sciences. The Sauls hope their gift can inspire others to do the same thing.

“I'm happy we’re able to make a lasting difference for another generation of students,” Saul said.

Saul says he’ll never forget the many ways that UMD changed his life. Now, it’s all about giving back.

“I owe my career to the University of Maryland, and the people who mentored me and worked with me,” he reflected. “This is a way that I can continue to make a difference and give something back.”

Written by Leslie Miller