- Details

-

Published: Tuesday, September 06 2022 00:01

In the world of startups, opportunity can come knocking in strange ways. Six years ago, Didier Depireux (Ph.D. ’91, physics) was doing research at the University of Maryland when he was approached by Sam Owen, a young scientist who said he’d developed a device to treat motion sickness. Depireux was skeptical but decided to check it out.

“Since I get very severe motion sickness, I made a deal with him,” Depireux recalled. “I said, ‘I’ll come over with my car and you can drive me around while I use the device. If I haven’t thrown up after 20 minutes while I’m in the back of the car reading, I’ll join the effort.’”

The two made plans to meet in Washington, D.C., on a muggy July afternoon.  Didier Depireux

Didier Depireux

“So, I go to Georgetown. The windows are down, it’s hot, it’s humid and I’m thinking I will not make it past the first turn,” Depireux explained. “Owen is driving and I’m in the back seat using his device and reading my cellphone. And for the first time in my life—and I’m over 50 years old—I was able to read in the back of a car and not get sick. I thought, ‘I need to join this, this is amazing.’”

Thanks to that strange summer ride-along, Depireux joined Owen in launching a startup called Otolith Labs to address inner ear-related conditions and their often debilitating symptoms. Otolith’s noninvasive vestibular system masking technology—designed for acute treatment of vestibular vertigo—received the FDA’s Breakthrough Device designation and clinical trials are ongoing, with support from investors including AOL founder Jack Davies and billionaire entrepreneur Mark Cuban.

All of this sets the stage for a major test that could lead to the startup’s ultimate goal—FDA approval as early as next year.

“In July we told the FDA we want to do a large-scale pivotal trial with hundreds of participants,” Depireux explained. “If all goes well, we’ll have a meeting next summer where the FDA will approve us and then the device will become available.”

For Depireux, it’s the latest step on a bigger mission that has guided his career.

Didier Depireux“It’s mostly relevance,” he explained. “I would like my life to make a difference, that’s the one thing that keeps me going.”

Didier Depireux“It’s mostly relevance,” he explained. “I would like my life to make a difference, that’s the one thing that keeps me going.”

From philosophy to physics

Depireux was raised in Belgium. A bright, thoughtful boy, he grew up with a strong interest in science and theory, thanks to his father, a physics professor, and his mother, a chemistry teacher.

“I was always very science-y,” Depireux recalled. “Initially, I wanted to become a philosopher and I read this 800-page book—I think it was Kant—and at the end of it I was like, ‘I still don’t know the answer, and I’m not even sure I understand the question anymore.’ That’s when I thought that’s not a good fit for me.”

Depireux eventually gravitated toward physics. After receiving his B.S. in physics from the University of Liège in Belgium in 1986, he began his graduate work in physics at the University of Maryland, where he focused on string theory and met Distinguished University Professor of Physics Sylvester James Gates Jr., who quickly became a mentor and friend.

“Jim had a huge impact on me. He was a fantastic person to work with and he had so much positive energy,” Depireux said. “I still remember late one night I was working on something, and I was stuck and I wrote to him, and he said, ‘I’ll come over, let’s work this out.’ So we had office hours at 10:30 p.m. just because I couldn’t solve a problem.”

Depireux earned his Ph.D. in 1991 and went on to do postdoctoral work in Quebec, Canada, before returning to College Park in 1994. Inspired by his wife Pamela, who was getting her Ph.D. in neuropharmacology, Depireux took on the challenge of modeling the brain and studying how it processes sound. By 2001, he was also teaching a gross anatomy class at the University of Maryland School of Medicine.

“I think, to this day, I am the only string theorist who has taught gross anatomy,” he reflected.

From his research on the brain and hearing, Depireux shifted his focus to tinnitus—disruptive ringing in the ears. He explored possible treatments and eventually teamed up with former UMD Bioengineering Professor Benjamin Shapiro who was already working on the drug delivery challenges Depireux was trying to solve.

“I wanted to get drug delivery to the ear but I didn’t know how to do it,” Depireux said. “He had this method with nanoparticles to deliver drugs and I had the target so we started working together.”

In 2013, the two launched Otomagnetics, a startup that has made major strides in developing noninvasive methods to treat inner ear diseases and more.

“We’ve gotten very nice results as far as drug delivery goes and Otomagnetics is still an ongoing concern,” Depireux explained, “But raising money for drug delivery is the real challenge, because to get drug delivery to the ear is going to take hundreds of millions of dollars, and that hasn’t happened yet.”

Going all-in on Otolith

Depireux balanced his time between Otomagnetics, his UMD research and teaching at the School of Medicine until 2016, when he experienced Owen’s experimental motion sickness device for the first time. Depireux saw so much potential with the device that he went all-in on Otolith.

“You have to have pretty strong resilience to join a startup—I went for a year and a half without a salary or anything,” Depireux explained. “It’s not like we didn’t have money, we just needed all of the money to develop the device, get the patents in, all of the things we had to do.”

Though Otolith started with a motion sickness device, its co-founders hoped to make an even bigger impact by developing a device for vertigo, debilitating dizziness often caused by problems in the inner ear.

And they had a plan.

“For tinnitus or ringing in the ears, some patients get relief from a noise masker—they can still perceive their tinnitus, but the noise masker allows them to ignore the tinnitus,” Depireux explained. “So Sam, my cofounder said, ‘Why don’t we come up with a noise masker for the vestibular system?’”

That’s exactly what they did. Their novel device, worn like a headband, treats vertigo by applying localized mechanical stimulation to the vestibular system through calibrated vibrations.

Depireux says he never would have made it this far without physics.

“My physics training really helped me,” he explained. “In physics, you have this huge problem and you have to break it down. If it’s intractable, you make it tractable, break it into small, simple things we can understand and then we can solve it.”

Promising results and personal stories

Clinical trials of Otolith’s investigational headband have yielded promising results. In the first of a series of ongoing clinical studies, 87.5% of the 40 participants reported a reduction in their vertigo within five minutes of turning on the device. But for Depireux, it’s the personal stories that are most rewarding.

“Somehow my phone number was listed as an emergency contact on clinicaltrials.gov, which I thought would be for emergencies only,” he said. “I’d have patients calling me in tears, telling me, ‘When my grandkids visit, I can finally bend down and pick them up, and it used to be that just bending down would send me into such vertigo that I would have to go to bed for days.’ Or ‘For the first time in years, I’ve been able to walk around the block.’ That’s what really motivates me.”

It's been Depireux’s goal all along—doing relevant research that changes people’s lives.

“We cannot help 100% of vertigo patients, no device does that,” he reflected. “But if we can help even half of those patients, that’s really my hope.”

Looking back on a career path that’s been anything but predictable, Depireux appreciates every challenge and setback that got him to where he is today.

“Something can feel like a failure when things go wrong, but then later you realize you really learned something from it,” he reflected. “I’m so grateful I was given the opportunity to come to the U.S. and study physics and do research in College Park, do this random walk in my career and finally end up doing something that I feel has given me great meaning in my life.”

Written by Leslie Miller

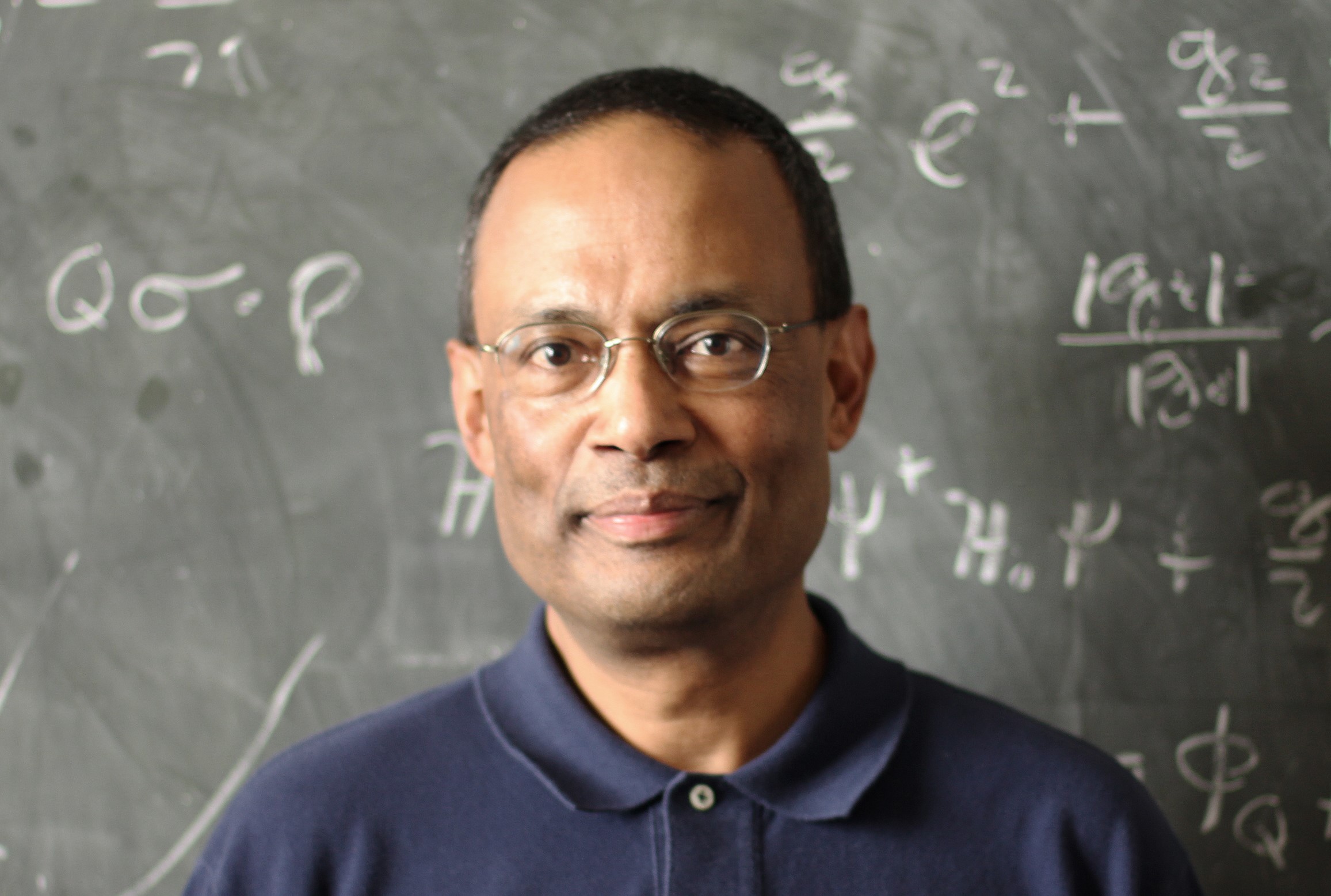

Sankar Das Sarma John Quinn (Ph.D., '58)—Das Sarma joined the UMD faculty in 1982. He was named a Distinguished University Professor in 1995, and in 2008 received the Kirwan Faculty Research Prize for his groundbreaking work in topological quantum computing.

Sankar Das Sarma John Quinn (Ph.D., '58)—Das Sarma joined the UMD faculty in 1982. He was named a Distinguished University Professor in 1995, and in 2008 received the Kirwan Faculty Research Prize for his groundbreaking work in topological quantum computing.