Nestled in the mountains of western South Dakota is the little town of Lead, which bills itself as “quaint” and “rough around the edges.” Visitors driving past the hair salon or dog park may never guess that an unusual—even otherworldly—experiment is happening a mile below the surface.

A research team that includes University of Maryland physics faculty members and graduate students hopes to lure a hypothesized particle from outer space to the town’s Sanford Underground Research Facility, housed in a former gold mine that operated at the height of the 1870s gold rush.

More specifically, they are searching for WIMPs—weakly interacting massive particles which are thought to have formed when the universe was just a microsecond old. The research facility suits this type of search because the depth allows the absorption of cosmic rays, which would otherwise interfere with experiments.

If WIMPs are observed, they could hold clues to the nature of dark matter and structure of the universe, which remain some of the most perplexing problems in physics.

Just getting started

The UMD team is led by Physics Professor Carter Hall, who has been looking for dark matter for 15 years. Excited by the prospect of observing unexplained physical phenomena, Hall joined the Large Underground Xenon (LUX) experiment, an earlier instrument at the Sanford Lab that attempted to detect dark matter from 2012 to 2016.

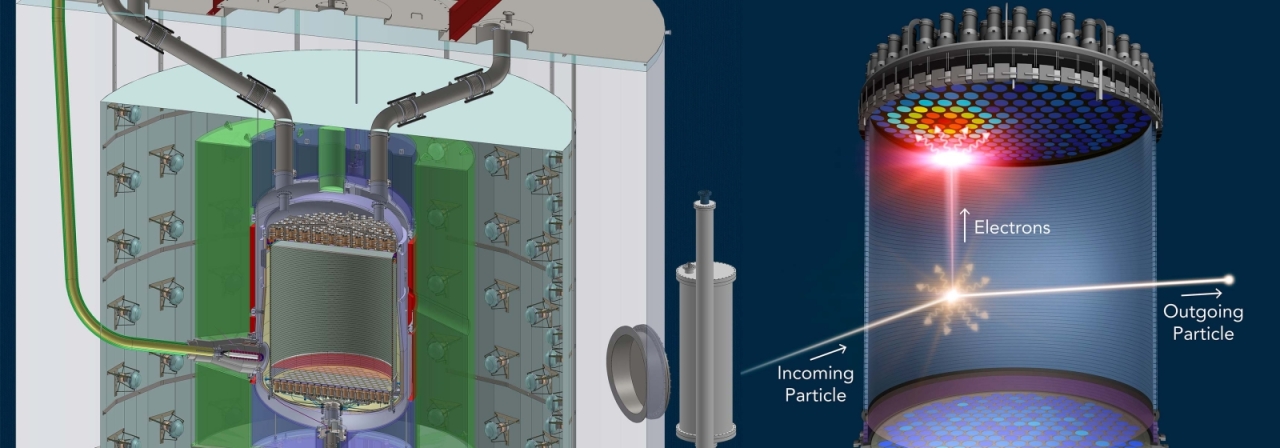

LUX was the most sensitive WIMP dark matter detector in the world until 2018. Its successor at Sanford, the new and improved LUX-ZEPLIN (LZ) experiment, launched last year. Hall believes LZ has even better odds of detecting or ruling out dark matter due to its significantly larger target. It’s specifically designed to search for WIMPs—a strong candidate for dark matter that, if proven to exist, could help account for the missing 85% of the universe’s mass.

Unlike experiments conducted at particle smashers like the Large Hadron Collider (LHC) in Switzerland, the LZ attempts to directly observe—rather than manufacture—dark matter. Anwar Bhatti, a research professor in UMD’s Department of Physics, said there are pros and cons to both approaches. He worked at the LHC from 2005 to 2013 and is now part of the LZ team at UMD.

Bhatti said the odds of finding irrefutable proof of WIMPs are slim, but he hopes previously undiscovered particles will show up in their experiment, leaving a trail of clues in their wake.

“There’s a chance we will see hints of dark matter, but whether it’s conclusive remains to be seen,” Bhatti said.

UMD physics graduate students John Armstrong, Eli Mizrachi, and John Silk are also part of this experiment, and the team published its first set of results in July 2022 following a few months of data collection. No dark matter was detected, but their results show that the experiment is running smoothly. Researchers expect to continue collecting data for up to five years.

“That was just a little taste of the data,” Hall said. “It convinced us that the experiment is working well, and we were able to rule out certain types of WIMPs that had not been explored before. We’re currently the world’s most sensitive WIMP search.”

Sparks in the dark

These direct searches for dark matter can only be conducted underground because researchers need to eliminate surface-level cosmic radiation, which can muddle dark matter signals and make them easier to miss.

“Here, on the surface of the Earth, we’re constantly being bathed in cosmic particles that are raining down upon us. Some of them have come from across the galaxy and some of them have come across the universe,” Hall explained. “Our experiment is about a mile underground, and that mile of rock absorbs almost all of those conventional cosmic rays. That means that we can look for some exotic component which doesn’t interact very much and would not be absorbed by the rock.”

In the LZ experiment, bursts of light are produced by particle collisions. Researchers then work backward, using the characteristics of these flashes of light to determine the type of particle.

The UMD research group calibrates the instrument that powers the LZ experiment, which involves preparing and injecting tritium—a radioactive form of hydrogen—into a liquefied form of xenon, an extremely dense gas. Once mixed, the radioactive mixture is pumped throughout the instrument, which is where the particle collisions can be observed.

The researchers then analyze the mixture’s decay to determine how the instrument responds to background events that are not dark matter. By process of elimination, the researchers learn the types of interactions are—and aren’t—important.

“That tells us what dark matter does not look like, so what we’re going to be looking for in the dark matter search data are events that don’t fit that pattern,” Hall said.

The UMD team also built, and now operates, two mass spectrometry systems that monitor xenon to ensure it isn’t poisoned by impurities like krypton, a gas found in the atmosphere. To detect dark matter scatterings, xenon must be extremely pure with no more than 100 parts per quadrillion of krypton.

Rewriting the physics playbook

The researchers will not know if they found dark matter until their next data set is released. This could take at least a year because they want the sensitivity of the second data set to significantly exceed that of the first, which requires a larger amount of data overall.

If detected, these WIMP particles would prompt a massive overhaul of the Standard Model of particle physics, which explains the fundamental forces of the universe. While this experiment could answer pressing questions about the universe, there is a good chance it will also create new ones. Hall thinks up-and-coming physicists will welcome that challenge.

“It would mean that a lot of our basic ideas about the fundamental constituents of nature would need to be revised in one way or another,” Hall said. “Understanding how that would fit into particle physics as we know it would immediately become the big challenge for the next generation of particle physicists.”

Written by Emily Nunez