- Details

-

Category: Research News

-

Published: Tuesday, November 18 2025 01:40

Physics is often about recognizing patterns, sometimes repeated across vastly different scales. For instance, moons orbit planets in the same way planets orbit stars, which in turn orbit the center of a galaxy.

When researchers first studied the structure of atoms, they were tempted to extend this pattern down to smaller scales and describe electrons as orbiting the nuclei of atoms. This is true to an extent, but the quirks of quantum physics mean that the pattern breaks in significant ways. An electron remains in a defined orbital area around the nucleus, but unlike a classical orbit, an electron will be found at a random location in the area instead of proceeding along a precisely predictable path.

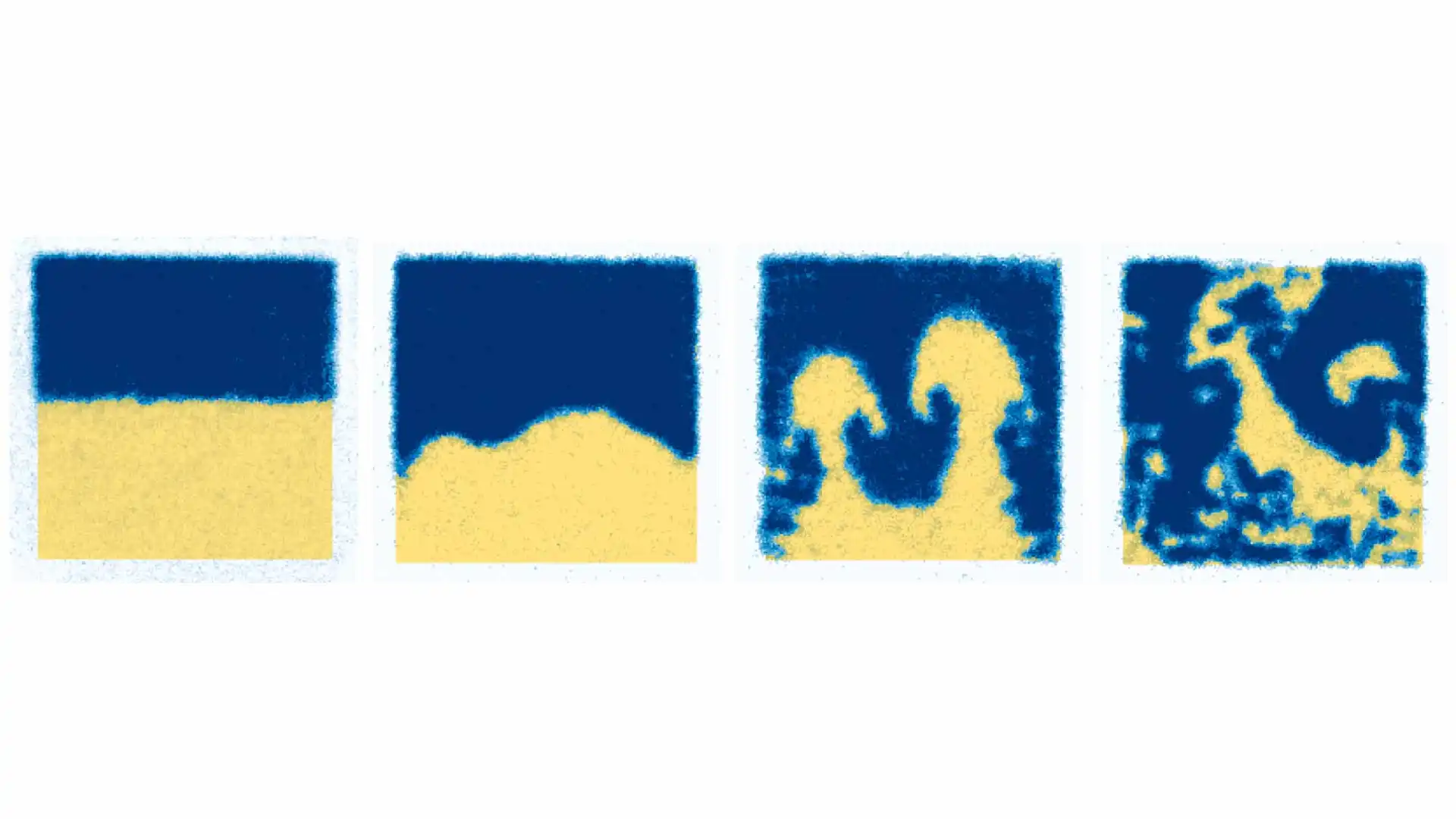

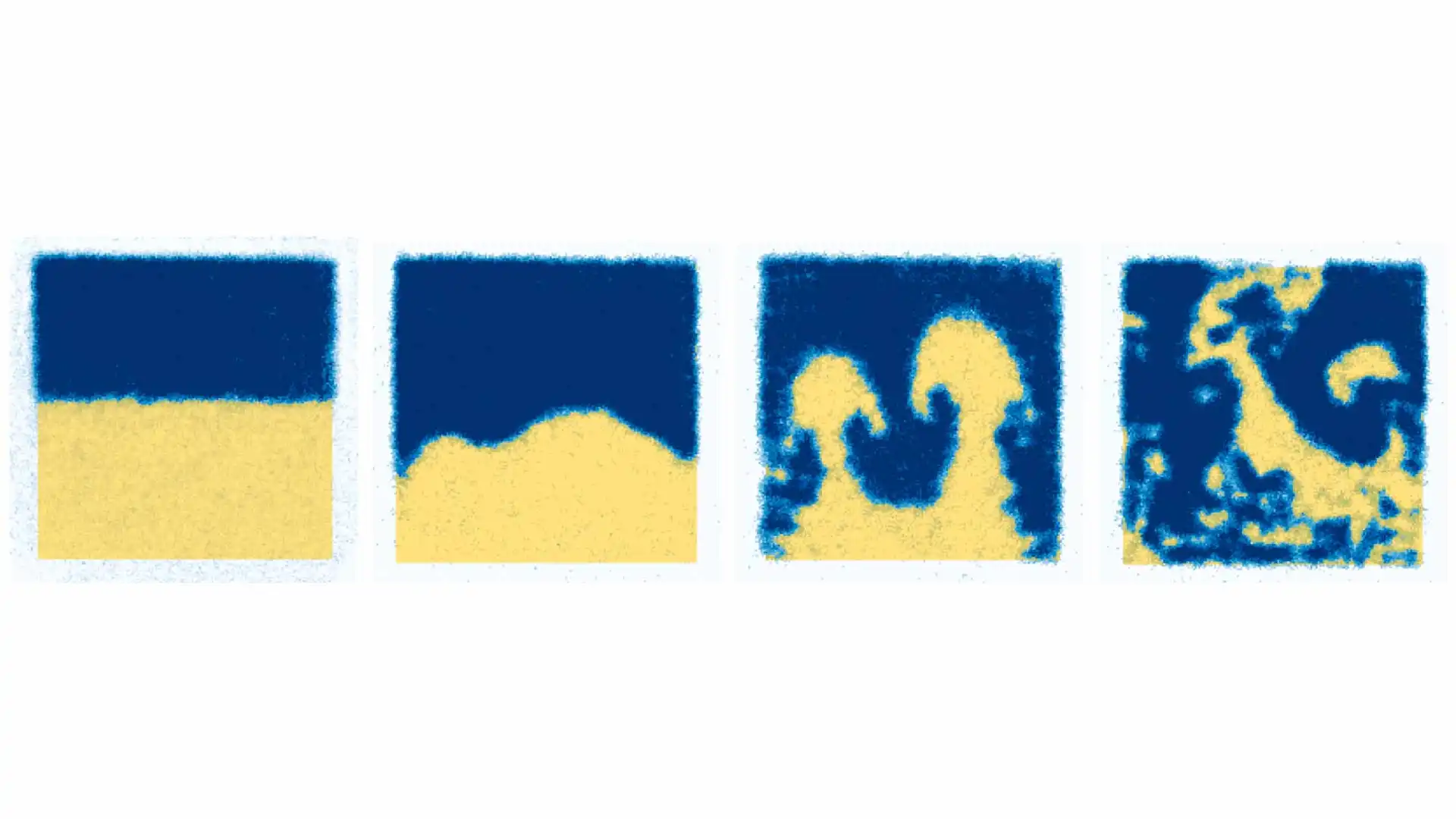

That electron orbits bear any similarity to the orbits of moons or planets is because all of these orbital systems feature attractive forces that pull the objects together. But a discrepancy arises for electrons because of their quantum nature. Similarly, superfluids—a quantum state of matter—have a dual nature, and to understand them, researchers have had to pin down when they follow the old rules of regular fluids and when they play by their own quantum rules. For instance, superfluids will fill the shape of a container like normal fluids, but their quantum nature lets them escape by climbing vertical walls. Most strikingly, they flow without any friction, which means they can spin endlessly once stirred up. A new experiment forces two quantum superfluids together and creates mushroom cloud shapes similar to those seen above explosions. The blue and yellow areas represent two different superfluids, which each react differently to magnetic fields. After separating the two superfluids (as shown on the left), researchers pushed them together, forcing them to mix and creating the recognizable pattern that eventually broke apart into a chaotic mess. (Credit: Yanda Geng/JQI)

A new experiment forces two quantum superfluids together and creates mushroom cloud shapes similar to those seen above explosions. The blue and yellow areas represent two different superfluids, which each react differently to magnetic fields. After separating the two superfluids (as shown on the left), researchers pushed them together, forcing them to mix and creating the recognizable pattern that eventually broke apart into a chaotic mess. (Credit: Yanda Geng/JQI)

JQI Fellows Ian Spielman and Gretchen Campbell and their colleagues have been investigating the rich variety of quantum behaviors present in superfluids and exploring ways to utilize them. In a set of recent experiments, they mixed together two superfluids and stumbled upon some unexpected patterns that were familiar from normal fluids. In an article published in Aug. 2025 in the journal Science Advances, the team described the patterns they saw in their experiments, which mirrored the ripples and mushroom clouds that commonly occur when two ordinary fluids with different densities meet.

The team studies a type of superfluid called a Bose-Einstein condensate (BEC). BECs form by cooling many particles down so cold that they all collect into a single quantum state. That consolidation lets all the atoms coordinate and allows the quirks of quantum physics to play out at a much larger scale than is common in nature. The particular BEC they used could easily be separated into two superfluids that provide a convenient way for the team to prepare nearly smooth interfaces, which were useful for seeing mixing patterns balloon from the tiniest seeds of imperfection into a turbulent mess. And the researchers didn’t only find classical fluid behaviors in the quantum world; they also spied the quantum fingerprints hidden beneath the surface. Using the uniquely quantum features of their experiment, they developed a new technique for observing currents along the interface of two superfluids.

“It was really exciting to see how the behavior of normal liquids played out for superfluids, and to invent a new measurement technique leveraging their uniquely quantum behavior,” Spielman says.

To make the two superfluid BECs in the new experiment, the researchers used sodium atoms. Each sodium atom has a spin, a quantum property that makes it act like a little magnet that can either point with or against a magnetic field. Hitting the cooled down cloud of sodium atoms with microwaves produces roughly equal numbers of atoms with spins pointing in opposite directions, which forms two BECs with distinct behaviors. In an uneven magnetic field, the cloud of the two intermingled BECs formed by the microwave pulse will sort itself into two adjacent clouds, with one effectively floating on top of the other; adjusting the field can make the superfluids move around.

This process was old hat in the lab, but, together with a little happenstance, it inspired the new experiment. JQI graduate student Yanda Geng, who is the lead author of the paper, was initially working on another project that required him to smooth out variations of the magnetic field in his setup. To test for magnetic fluctuations, Geng would routinely turn his cloud of atoms into the two BECs and take a snapshot of their distribution. The resulting images caught the eye of JQI postdoctoral researcher Mingshu Zhao, who at the time was working on his own project about turbulence in superfluids. Zhao, who is also an author of the paper, thought that the swirling patterns in the superfluids were reminiscent of turbulence in normal fluids. The snapshots from the calibration didn’t clearly show mushroom clouds, but something about the way the two BECs mixed seemed familiar.

“This is what you call serendipity,” Geng says. “And if you have somebody in the lab who knows what could have happened, they immediately could say, ‘Oh, that's something interesting and probably worth pursuing scientifically.’”

The hints kept appearing as Geng’s original experiment repeatedly hit roadblocks. After months of working on the project, he felt like he was banging his head against a wall. One weekend, another colleague, JQI postdoctoral researcher Junheng Tao, encouraged Geng to mix things up and spend some time exploring the hints of turbulence. Tao, who is also an author of the paper, suggested they intentionally create the two fluids in a stable state and check if they could see patterns forming before the turbulence erupted.

“It was a Sunday, we went into the lab, and we just casually put in some numbers and programmed the experiment, and bam, you see the signal,” Geng says.

The magnetic responses of the two BECs gave Geng and Tao a convenient way to control the superfluids. First, they let magnetism pull the two BECs into a stable configuration in which they lie flush against each other, like oil floating on water. Then, by reversing the way the magnetic field varied across the experiment, the BECs were suddenly pulled in the opposite direction, instantly producing the equivalent of water balanced on top of oil.

After adjusting the field, Geng and Tao were able to take just a single snapshot of the mixing BECs. To get the image, they relied on the fact that the BECs naturally absorb different colors of light. They flashed a color that interacted with just one of the BECs, so they could identify each BEC based on where the light was absorbed. Inconveniently, absorbing the light knocked many atoms out of the BECs, so snapping the image ended the run of the experiment.

By waiting different amounts of time each run, they were able to piece together what was happening as the two BECs mixed. The results revealed the distinctive formation of mushroom clouds that ultimately degenerated into messy turbulence. The researchers determined that despite the many stark differences between BEC superfluids and classical fluids, the BECs recreated a widespread effect, called the Rayleigh-Taylor instability, that is found in normal fluids.

The Rayleigh-Taylor instability describes the process of two distinct fluids needing to exchange places, such as when a dense gas or liquid is on top of a lighter one with gravity pulling it down. The instability produces a pattern of growth of small imperfections in an almost stable state that devolves into unpredictable turbulent mixing. It occurs for water on top of oil, cool dense air over hotter air (as happens after a big explosion) and when layers of material explode out from a star during a supernova. The instability contributes to the iconic “mushroom clouds” observed in the air layers moving above explosions, and similar shapes were found in the BEC.

“At first it's really mind-boggling,” Geng says. “How can it happen here? They’re just completely different things.”

With a little more work, they confirmed they could reliably recreate the behavior and showed that the superfluids in the experiment had all the necessary ingredients to produce the instability. In the experiment, the researchers had effectively substituted magnetism into the role gravity often plays in the creation of the Rayleigh-Taylor instability. This made it convenient to flip the direction of the force at a whim, which made it easy to begin with a calm interface between the fluids and observe the instability balloon from the tiniest seeds of imperfection into turbulent mixing.

The initial result prompted the group to follow up on the project with another experiment exploring a more stable effect at the interface. Instead of completely flipping the force, they kept the “lighter” BEC on top—like oil, or even air, resting on water. By continuously varying the magnetic field at a particular rate, they could shake the interface and create the equivalent of ripples on the surface of a pond. Since the atoms in each BEC all share a quantum state, the ripples have quantum properties and can behave like particles (called ripplons).

But despite the clear patterns resembling mushroom clouds and ripples of normal fluids, the quantum nature of the BECs was still present throughout the experiment. After seeing the familiar behaviors, Geng began to think about the quantum side of the superfluids and turned his attention to something that is normally challenging to do with BECs—measuring the velocity of currents flowing through them.

Geng and his colleagues used the fact that the velocity of a BEC is tied toits phase—a wavelike feature of every quantum state. The phase of a single quantum object is normally invisible, but when multiple phases interact, they can influence what researchers see in experiments. Like waves, if two phases are both at a peak when they meet, they combine, but if a peak meets a trough, they instead cancel out. Or circumstances can produce any of the intermediate forms of combining or partially cancelling out. When different interactions occur at different positions, they create patterns that are often visible in experiments. Geng realized that at the interfaces in his experiment the wavefunctions of the two BECs met and gave them a unique chance to observe interfering BEC phases and determine the velocities of the currents flowing along the interface.

When the two BECs came together in their experiments, their phases interfered, but the resulting interference pattern remained hidden. However, Geng knew how to translate the hidden interference pattern to something he could see. Hitting the BECs with a microwave pulse could push the sodium atoms into new states where the pattern could be experimentally observed. With that translation, Geng could use his normal snapshot technique to capture an image of the interference between the two phases.

The quantum patterns he saw provide an additional tool for understanding the mixing of superfluids and demonstrate how the familiar Rayleigh-Taylor instability pattern found in the experiment had quantum patterns hidden beneath the surface. The results revealed that despite BEC superfluids being immersed in the quantum world, researchers can still benefit from keeping an eye out for the old patterns familiar from research on ordinary fluids.

“I think it's a very amazing thing for physicists to see the same phenomenon manifest in different systems, even though they are drastically different in their nature,” Geng says.

Original story by Bailey Bedford: https://jqi.umd.edu/news/when-superfluids-collide-physicists-find-mix-old-and-new

In addition to Campbell, who is also the Associate Vice President for Quantum Research and Education at UMD; Spielman; Geng; and Zhao, co-authors of the paper include former JQI postdoctoral researcher Shouvik Mukhherjee and NIST scientist and former JQI postdoctoral researcher Stephen Eckel.