Conducting Quantum Experiments in the ‘Coolest’ Lab on Campus

- Details

- Published: Tuesday, February 03 2026 01:40

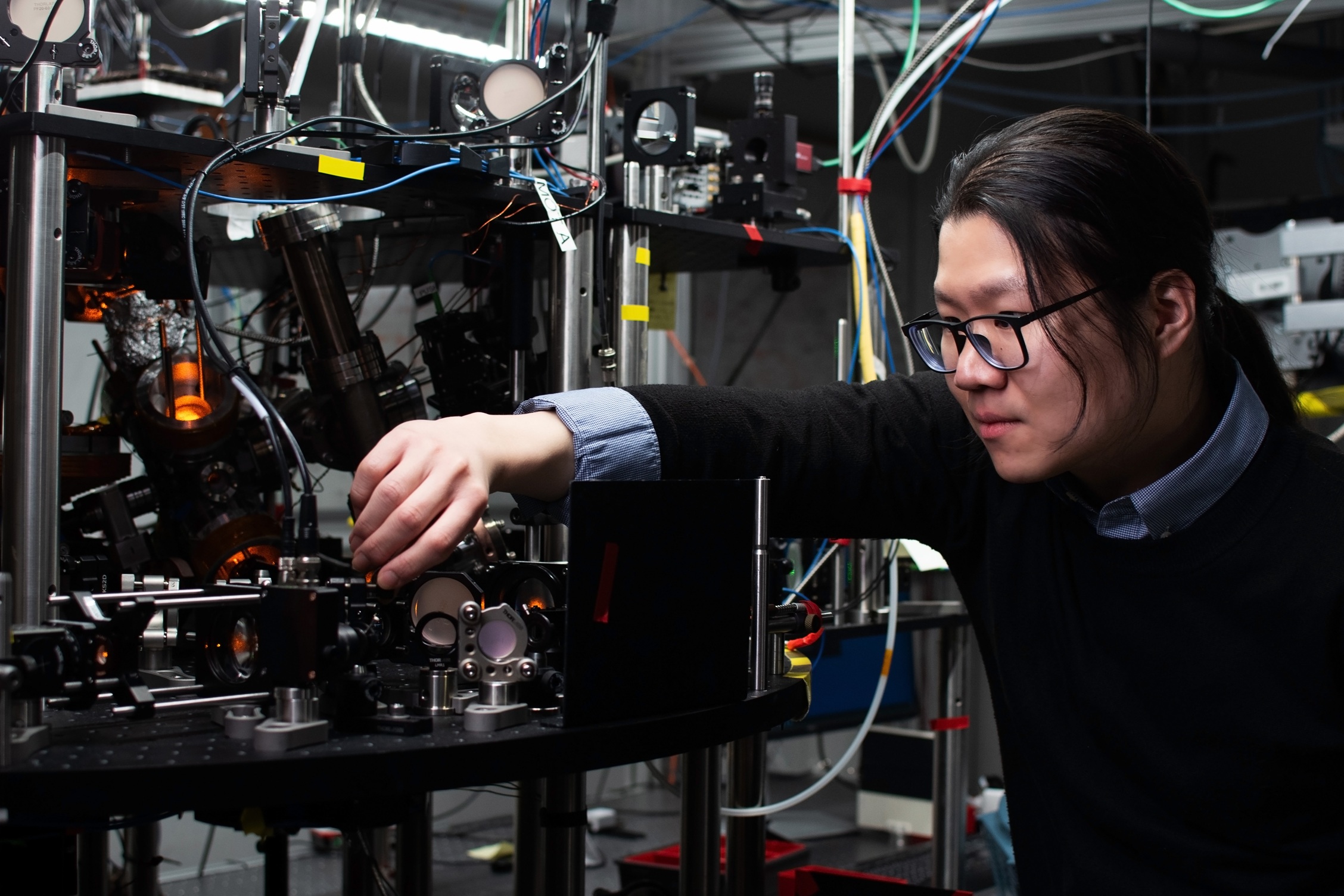

When University of Maryland physics Ph.D. candidate Yanda Geng tells people he works at the ‘coolest’ lab on campus, he’s not exaggerating. In his laboratory at the Joint Quantum Institute (JQI), atoms are cooled to 100 nanokelvin—about one billionth of a degree above absolute zero and roughly 1,000 times colder than the quantum systems used in superconducting quantum computers. Yanda Geng at work in the lab. Credit: Rahul Shrestha

Yanda Geng at work in the lab. Credit: Rahul Shrestha

In these extreme conditions, something bizarre happens. Atoms stop acting like individual particles and instead merge into a single quantum blob called a Bose-Einstein condensate (BEC). BECs contain millions of atoms that behave according to quantum mechanics rather than classical physics, and they reveal quantum dynamics on a scale large enough to observe without the extreme difficulty of studying single atoms or photons.

“Simply put, we use laser cooling and trapping techniques to cool atoms down to a very cold temperature, changing the atoms into a different type of matter,” Geng said.

Advised by Adjunct Professor of Physics Ian Spielman and Associate Vice President for Quantum Research and Education Gretchen Campbell, Geng used microwaves to split the BEC into two different superfluids—liquids that flow without friction.

“Unlike regular fluids that eventually stop moving because of friction, superfluids can flow forever,” Geng explained. “For example, if you have superfluid in a bucket and rotate that bucket, the superfluid inside won’t follow the bucket because it doesn’t really ‘feel’ the motion of the wall.”

Like oil and water, these two superfluids cannot mix. But Geng and postdoctoral researcher Junheng Tao discovered interesting swirling patterns as they pushed the superfluids together—the distinctive mushroom-shaped plumes were eerily similar to what happens when galaxies collide, volcanoes erupt or nuclear fusion occurs. Called the Rayleigh-Taylor instability (RTI), this phenomenon had been observed in classical fluids before, but never in superfluids.

“I remember quite distinctly when this data was presented at group meeting: it was a surprise,” noted Spielman. “Several of the cold atom students had been talking with me about measuring fluid dynamical instabilities for some time, but the first RTI data was taken in secret on a weekend, and neither Gretchen nor I knew it was coming!”

For Geng, the findings confirm something profound about the universe: some laws of physics are so fundamental that they work the same everywhere, from cosmic scales to the quantum realm. Finding the same patterns in the quantum world and the everyday world helps scientists understand where the rules of classical physics end and where unique quantum behaviors begin. Geng and the team published the discovery in the journal Sciences Advances in August 2025.

“It’s kind of amazing to see that this [Rayleigh-Taylor instability] is everywhere, and that the ingredients you need to make it happen aren’t that difficult to put together,” Geng noted. “It’s a pattern with extremely simple origins, something you can find in countless other systems under countless different conditions.”

The journey to cold atom physics

Growing up, Geng was inspired by his uncle, a high-energy physicist, to pursue fundamental questions about how the universe works. After earning his undergraduate degree in physics at Nanjing University in 2020, Geng began looking for graduate schools with atomic physics programs. UMD quickly became a top choice.

“UMD was really a dream school because of its collaboration with [the U.S. National Institute of Standards and Technology] through JQI,” Geng recalled. “I was happy to accept an offer from UMD. Even when a Berkeley professor during my search warned that what I was interested in—ultracold neutral atoms—was ‘really difficult physics,’ I was more confident than ever that this is what I want to do.”

When he began working with Spielman and Campbell in his second year, Geng inherited an experiment from previous students that quickly needed major repairs and upgrades. The experiment itself was a marvel of complexity: four laser tables spanning a 20-foot-by-30-foot lab, requiring expertise in optics, vacuum systems, electronics and even plumbing for the water-cooling system. Everything was controlled by Python programs and code largely written by Geng himself, drawing on the programming skills he learned in high school.

“You have to make sure all subsystems work, and they have to all work at the same time. For the first two years, I worked to optimize each component to achieve the reliability needed for publishable research,” Geng said.

Advocacy in academia

Over the years, Geng has also embraced a leadership role, serving on the department’s Graduate Student Committee, where he organized outreach and social events to help bridge communication gaps between students and faculty members. Geng is particularly committed to supporting new graduate students studying cold atomic physics, emphasizing both the immense challenges and rewards in the field.

“I remember how I was when I first started here,” Geng explained. “Having some guidance about what to expect as a graduate researcher in cold atomic physics would have really helped me, so I try to pass along my experiences about things like how to interact with a PI and how to be patient with projects. It’s my goal to be transparent and give everyone a realistic picture of what academic research environments can look like.”

As he approaches his graduation, Geng plans to continue doing research that makes an impact beyond the lab.

“I want to see my work directly connected to people’s lives,” Geng said. “Even though my research is very fundamental, what I’ve found is actually very universal in some ways. I like fundamental research that explores the secrets of the universe, but I’m also interested in photonics applications like with biosensors or precision measurement work like atomic clocks—research that can potentially change people’s lives.”

Written by Georgia Jiang